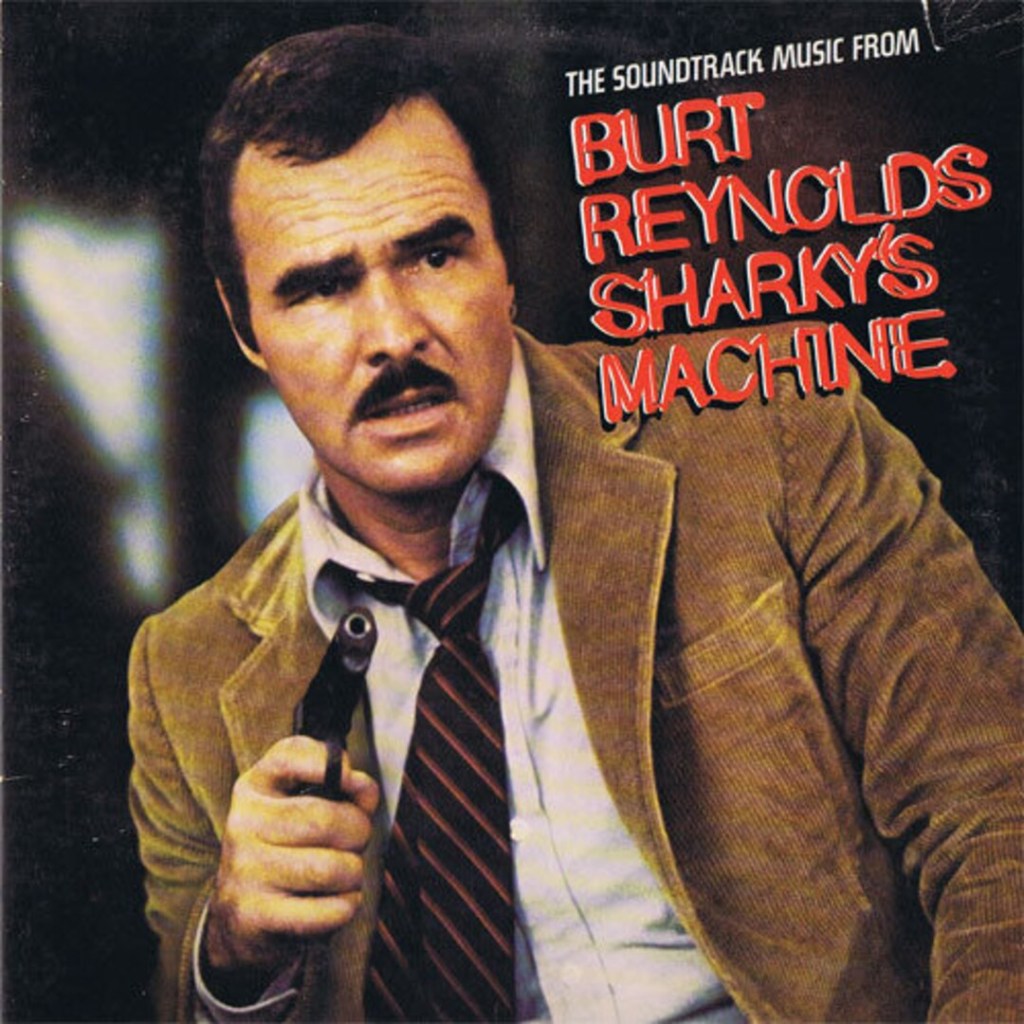

I’ve known of Burt Reynolds’ Sharky’s Machine from the very beginning of my awareness of film. Mostly because of its title and for Dar Robinson’s famous – though decidedly under-photographed – stunt. Many years later as an adult, I sought the film out and bought it in the unfortunate snap case. And sadly the print on the disc has “been modified to fit my TV”. Regardless, a more recent viewing of this neo-noir has proved to me that the film stands up.

When Burt’s pal Clint Eastwood had a hit with Every Which Way But Loose (1978), Burt told Clint he was entering his territory with the comedy. Burt then said he would one day return the favour by making a serious film he jokingly referred to as Dirty Harry Goes to Atlanta. When Sharky’s Machine went into production, Eastwood sent his buddy a wire; “You weren’t kidding!”.

I went through a six-month stretch during which I scoured every garage sale, every thrift store and every antique mall I could in two countries for a vinyl copy of the soundtrack for the film, Breezy, the film that came out of nowhere, staggered me and earned its own lodging here at Vintage Leisure. I had no luck locating this rarity. I recruited my youngest son to also be on the lookout every time he went to one of the two locations of his favourite record store in the city in which he lived. For months he also searched. This hunt resulted in him scoring for me many cool soundtrack LPs from some of my favourite films; 9 1/2 Weeks, The Big Town, Tequila Sunrise, The Wanderers, Under the Boardwalk, Homeboy, Shaft and others. One of the records I was thrilled to have him find for me was the soundtrack for Sharky’s Machine. And, yes, eventually he did stumble on Breezy; it was a day my family and I will never forget. For the Sharky’s Machine soundtrack, Burt made a decision that was monumental but that was underappreciated at the time and has remained so over the years. I’m here to fix that.

The story of the music for the film starts with Thomas Lesslie Garrett. The man known as “Snuff” Garrett had been an in-house producer at Liberty Records and then branched out on his own to work with…basically everybody. He gravitated towards countrypolitan music and eventually produced the country-oriented soundtrack for the aforementioned Every Which Way But Loose and he also produced the soundtrack for Smokey and the Bandit II. Burt gave Snuff the job of assembling the soundtrack for Sharky’s Machine and Garrett joined with Al Capps. Capps had worked for years as Music Supervisor at my beloved American International Pictures and then had joined Garrett to work on the music for many films.

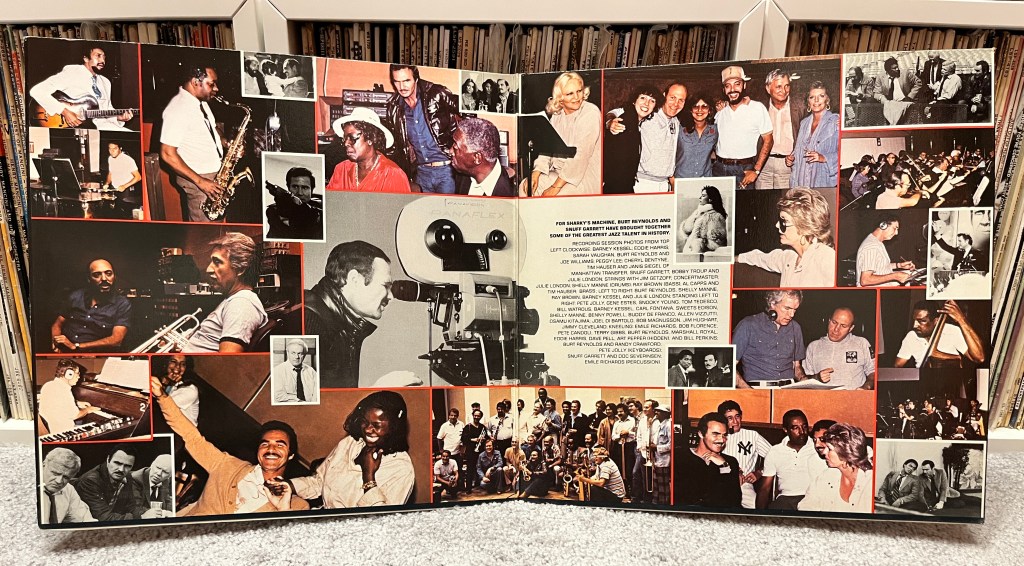

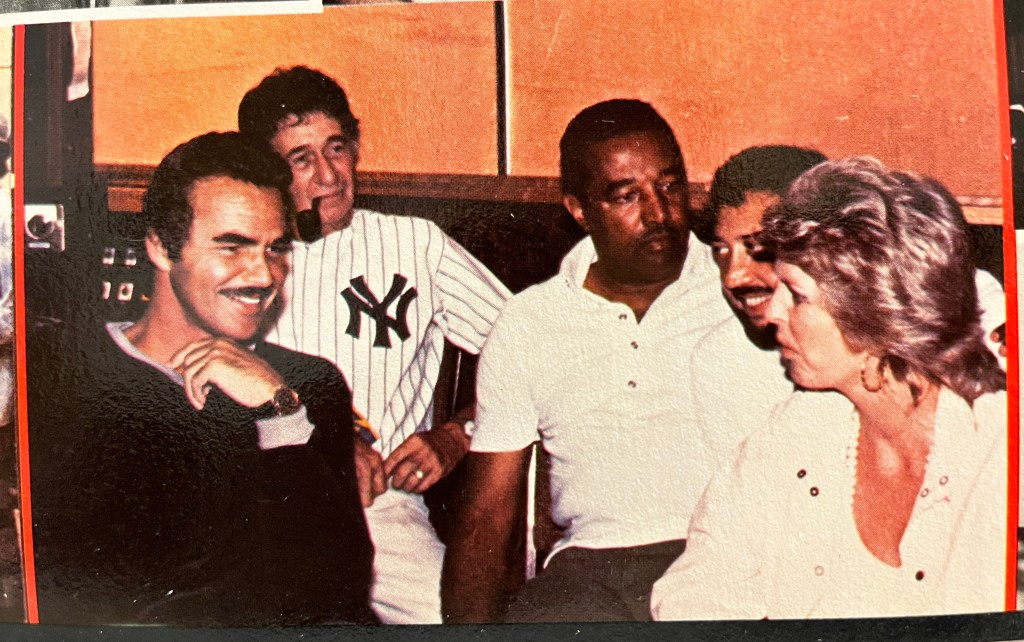

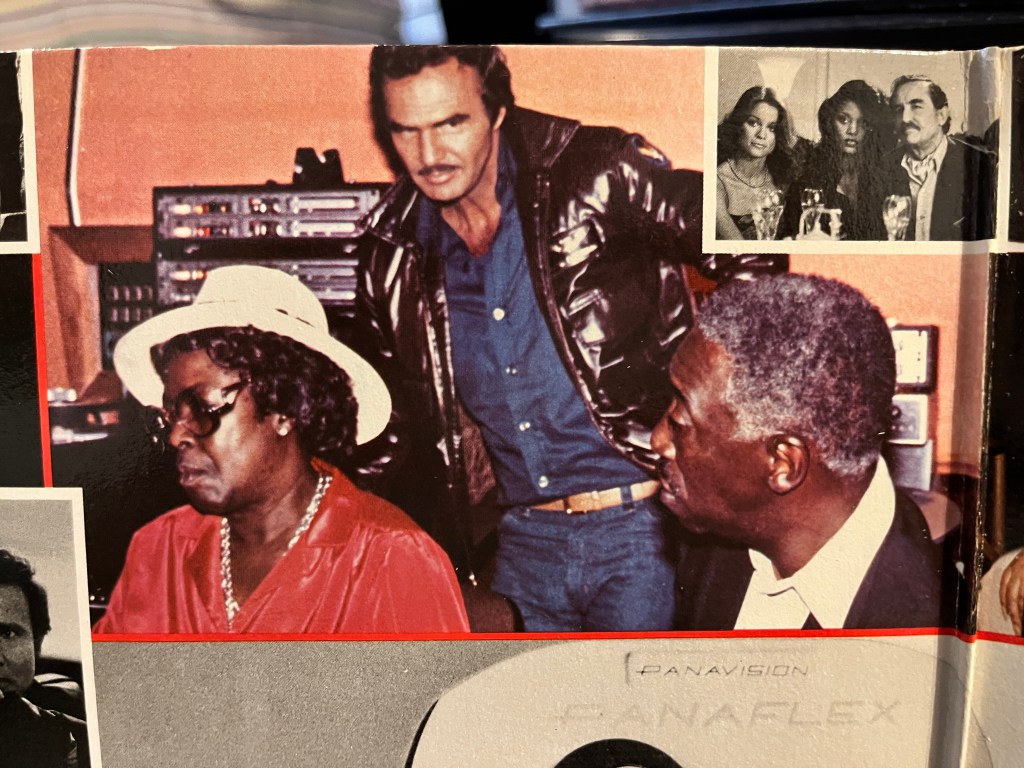

What Reynolds, Garrett and Capps did for the music for Sharky’s Machine was quite historic; they assembled a formidable team of artists – many of them jazz legends – and brought them together in the studio to create new songs for use in the film and on the album.

The early scenes of the film are gritty and well-directed by Burt, featuring the fine helicopter photography that bookends the movie. I’ll admit, I think the exuberance of the first track is ever so slightly ill-fitted to the action on screen but it’s a great tune. “Street Life” was the title track to the Crusaders’ 1979 album. For the recording of the song, the Crusaders brought in singer Randy Crawford to provide vocals and the song was a Top 40 hit, serving as a last hurrah for the Crusaders. I am happy to report that Herb Alpert presented an instrumental version of this song that same year on my all-time favourite album, Rise. The Sharky’s Machine album opens where the film does, with this soundtrack version for which Crawford was asked to provide fresh vocals over a new and robust treatment of the song by one Doc Severinsen of the Tonight Show. It was this updated version of “Street Life” that Quentin Tarantino used on the soundtrack of his 1997 film, Jackie Brown.

Burt Reynolds simply knows; he understood many things, jazz included. For this record he made much use of two legends near and dear to my heart. First up is Bobby Troup who shows up in my world via the TV show Emergency! and through his prodigious appearances as composer and performer throughout the wonderful Ultra-Lounge CD series from Capitol in the 90s. Troup’s enduring legacy is secured due to his having written the standard “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66”, which is essayed here by the Manhattan Transfer.

A song used as a theme throughout the film is the venerable Rodgers & Hart composition “My Funny Valentine”. One could surmise that the lyric applies to Sharky falling for the prostitute, Dominoe. The first version presented on this record is by Chet Baker and this recording apparently is a new one specifically for this album, though information is scant on how Baker came to provide new vocals for this track. Baker was based mainly in Europe at the time but Burt Reynolds says in his first memoir that, for the soundtrack, he “even slipped trumpeter Chet Baker into the country and made him sing”. The next track is one of two instrumentals presented in the film and on the soundtrack album by Doc Severinsen.

Another savvy move from Burt and Snuff was bringing in legendary singer Sarah Vaughan. By the 1980s, “The Divine One” was coming to the end of her alliance with Pablo Records and indeed to the end of her recording career. Sharky’s Machine contains two of her final recordings. “Love Theme from Sharky’s Machine” closes the first side and was co-written by Bobby Troup. Later, Sassy will close the record in a duet with the big man, Joe Williams. Mighty Joe sang with the Count Basie Orchestra in the 1950s and he gifted the world with the immortal recording “Every Day I Have the Blues” in 1955. Joe is another alumni of the Old School present on this record and in addition to his duet with Vaughan, he takes a solo to start the second side. “8 to 5 I Lose” is another of the five original songs on this album. And this leads us to the other legend near and dear to my heart that I mentioned earlier.

As most of you know, Bobby Troup was married to singer Julie London, who joined her husband on that 70s paramedic TV drama and who was of course a celebrated chanteuse, recording many smoky vocal albums for Snuff Garrett and Liberty Records in the Fifties and Sixties. Garrett reached out to Julie to record a tune for this album but she was extremely reluctant. According to her biographer, Michael Owen, London had her thyroid gland removed in 1979 and that, along with her years of nicotine and alcohol intake had taken a toll on her voice. Julie had already decided that her singing days were over when Garrett called to ask her to join the venerable line-up he had assembled for the music for Sharky’s Machine. Without a moment’s hesitation, she told Snuff she would do whatever he wanted.

It was a great help to Julie to see some old running mates in the studio. Studio greats and all-world jazzbos Barney Kessel on guitar, Shelley Manne on drums and Ray Brown on bass support Julie on the final recording of her exemplary career, “My Funny Valentine” and for additional support – for self-critical Julie this was “terror magnified to a new degree” – she brought in her daughter, Lisa, to sit opposite her during recording. And incidentally, Sharky’s Machine is something of a Troup family affair when you add in the fact that Cynnie Troup, Bobby’s daughter, served as script supervisor on the film. If for no other reason, the Sharky’s Machine soundtrack is more than notable for this coda to Julie’s career.

And then there’s Peggy Lee. Like others on this record, Lee is a luminary from a previous era, one still plying her trade at the time despite advanced age and health issues. In the late 70s, she had suffered paralysis in the right side of her face and the strength of her vocal cords began to fluctuate and she developed a deeper husk. It’s been noted that her voice was strongest in the early 1980s and this is when Snuff and Burt brought her in to record “Let’s Keep Dancing”. The record closes as the films does with the gentle duet mentioned earlier, one featuring Vaughan and Williams, “Before You”.

Cliff Crofford was an old-time honky tonk songwriter and steel guitar player. As the years rolled, somehow he got to writing songs for western-themed Hollywood movies. In a further Clint Eastwood connection, Crofford contributed songs to Clint’s films Bronco Billy, Every Which Way But Loose, Any Which Way You Can and Honkytonk Man. Not to mention Burt’s films Smokey and the Bandit II and The Cannonball Run. Cliff once had recorded for Liberty and here is likely where the Snuff Garrett connection lies. A younger man than Cliff but one who shows up in the same places is songwriter and musician John Durrill (The 5 Americans, “Western Union”).

In addition to recruiting all this illustrious vocal talent for the record, Snuff and Burt provided them with original material. Four songs on this record are credited as having been written by Cliff Crofford, John Durrill, Snuff Garrett and Bobby Troup – “Love Theme from…”, “8 to 5 I Lose”, “Let’s Keep Dancing” and “Sharky’s Theme” played by noted tenorman Eddie Harris. A fifth, “Before You”, was penned by the three men minus Bobby. This helps prove my point. Burt Reynolds and Snuff Garrett planned and executed something incredibly distinctive with the soundtrack music for Sharky’s Machine. On top of all this notability, it is an excellent record.

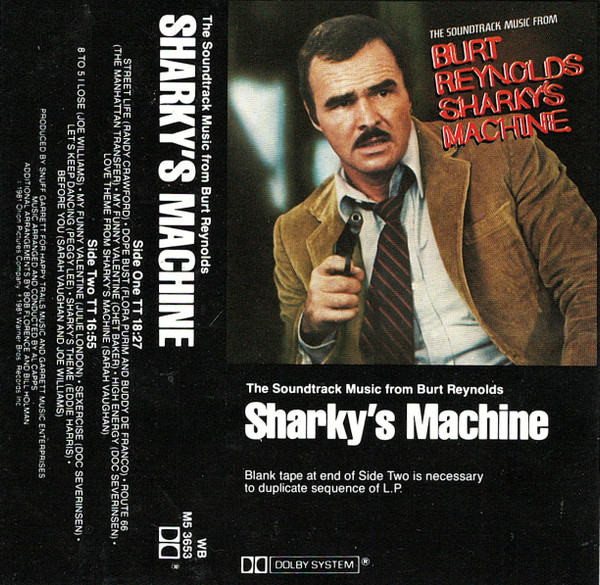

The Soundtrack Music from Burt Reynolds’ Sharky’s Machine (XBS 3653 – 1981) from Warner Bros. Records

Produced by Snuff Garrett

Side One: “Street Life” – Randy Crawford, “Dope Bust” – Flora Purim and Buddy De Franco, “Route 66” – The Manhattan Transfer, “My Funny Valentine” – Chet Baker, “High Energy” – Doc Severinsen, “Love Theme from Sharky’s Machine” – Sarah Vaughan

Side Two: “8 to 5 I Lose” – Joe Williams, “My Funny Valentine” – Julie London, “Sexercise” – Doc Severinsen, “Let’s Keep Dancing” – Peggy Lee, “Sharky’s Theme” – Eddie Harris, “Before You” – Sarah Vaughan and Joe Williams

Personnel includes: Art Pepper, alto saxophone // Buddy De Franco, clarinet // Ray Brown, double bass (acoustic) // Shelley Manne, drums // Bud Shank, flute // Barney Kessel, guitar // Tommy Tedesco, guitar // Bill Perkins, tenor saxophone // Eddie Harris, tenor saxophone // Carl Fontana, trombone // Jimmy Cleveland, trombone // Doc Severinsen, trumpet // Pete Candoli, trumpet // Joe Williams, vocals // Julie London, vocals // Peggy Lee, vocals // Sarah Vaughan, vocals // Chet Baker, vocals // The Manhattan Transfer, vocals.

Sources

- Reynolds, Burt. My Life. (1994)

- Owen, Michael. Go Slow: The Life of Julie London. (2017)