“All that was left were fragments…echos of long-dead voices reaching from the void on the other side of the din on the freeway. And yet, by painstakingly piecing together these hundreds of scattered fragments, I had managed to reconstruct a picture of what had happened. A picture that, while lacking in some details, was on the whole remarkably clear. How could that picture have remained buried for so long? There had clearly been a willful campaign to suppress the facts of the case, and to discredit and harass key witnesses…recent writers and researchers…ignored the evidence, plain on the face of the contemporary documents, which pointed an unequivocal finger at an insignificant, sloop-shouldered man in glasses. A man who had, by conventional wisdom, been treated as a bizarre footnote in the case.”

Black Dahlia, Red Rose

by Piu Eatwell (2017)

For years I have been a fan of film noir. Every now and then I will immerse myself in the genre, watching old favourites and seeking out ones I’ve never seen. Those of you who know whereof I speak will understand when I say that the atmosphere of these films is so appealing; the dire, often hopeless circumstances, the inevitability of prison or death and the omnipresent hints of darkness in the underbelly of the urban jungle. Sometimes for more vivid depictions of this darkness, I will turn to neo-noir and their ability as newer films to be more forthcoming regarding depravity.

One such pursuit lead me to Brain De Palma’s 2006 film The Black Dahlia, based on James Ellroy’s novel telling of a pair of LAPD detectives dealing with events surrounding the real life 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short who came to be christened The Black Dahlia. It was a very small leap for me to begin to want to learn more about Short’s horrific murder and to begin looking for a book to read. I landed on the one we’re looking at today. It’s written by British-Indian Piu Eatwell, an author based in France and it’s her fourth and to date her most recent book.

For those who don’t know, on January 15, 1947, Elizabeth Short’s mutilated and bisected body was found in the grass next to a sidewalk in Leimert Park in Los Angeles sparking years of investigation that resulted in zero results making it perhaps the most notable unsolved crime in American history. More than this though, this harrowing tale is historically significant as it brings together in unfortunate harmony many and varied strands of Los Angeles history including elements of film noir, the corruption that infested the LAPD at the time, organized crime, the birth of psychological profiling and the heinous nature of sex crimes. Twenty years later, the Manson murders had the city on edge with many afraid to walk the streets for fear of being targeted for horrible death at the hands of so-called hippies. In much the same way, the unsolved Black Dahlia murder disturbed Angelenos in the late 40s and served as a warning for the female population, becoming symbolic of the things that could happen to would-be starlets when they arrived in Hollywood vulnerable and ripe for abuse and exploitation. It put an ignominious end to the image of Los Angeles, California as a shining and glorious place with endless opportunities for all.

Eatwell’s book on the subject can be considered ideal for learning about the investigation that took place and how it was handled by police and particularly how it was covered by the press. It was the very epitome of sensational and the major papers had Dahlia cover stories daily for weeks after the discovery of the body. The author notes that the January 15th Extra edition of the Los Angeles Examiner headlined “Fiend Tortures, Kills Girl” sold more copies than the edition that announced the bombing of Pearl Harbor. She also introduces the reader to legendary newspaper players of the time and the fact that their investigative journalism was at times just as effective as the investigations of the police. Eatwell describes one reporter who hoped to get information from Short’s mother as calling the poor woman – who did not know her daughter had been killed – claiming Elizabeth had won a beauty contest and pumping her for details. Near the end of the call, the reporter dropped the bomb that he had been lying and told Mrs. Short about Elizabeth’s horrible fate.

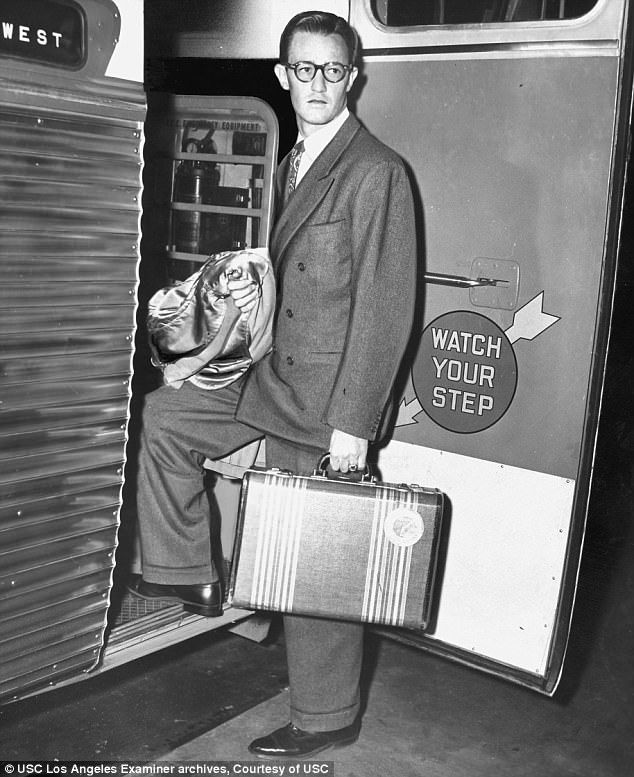

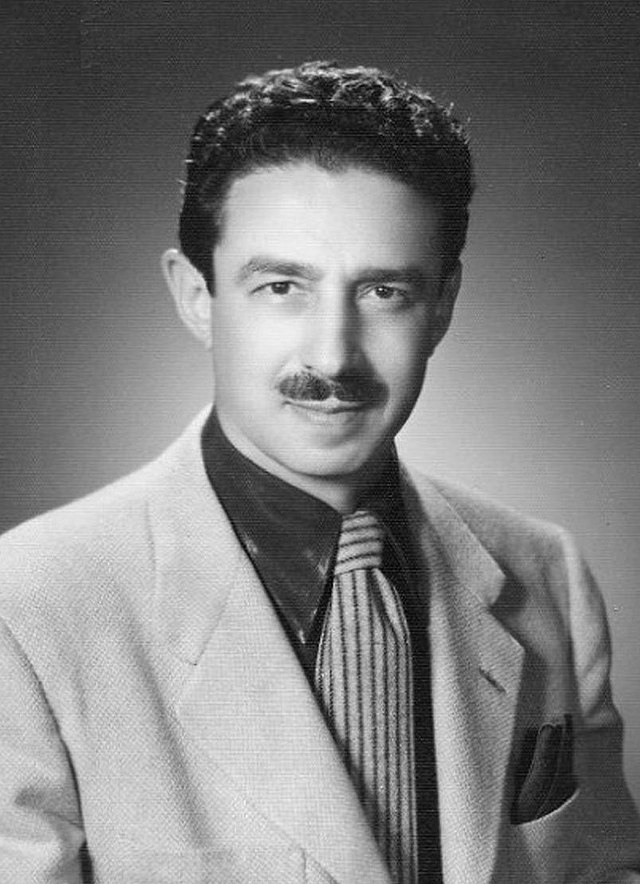

Black Dahlia, Red Rose provides a detailed account of the investigation of prime subject Leslie Dillon, a slight, bespectacled bellhop and erstwhile pimp who had initially called the papers to offer help with the investigation. Piu Eatwell takes pains to explain Dillon’s psychological makeup and his possible motivations. Also discussed is his cross-country interview with police psychologist Dr. Paul De River during which Dillon revealed intimate knowledge of the Short murder particularly his offering info about the corpse that was specifically kept from the public; things only the killer would know. Also explained are Dillon’s connections to Mark Hansen, the Danish businessman with mob ties who owned the Florentine Gardens night club. These two are scrutinized intently and their manueverings in the darkness are brought to stark light.

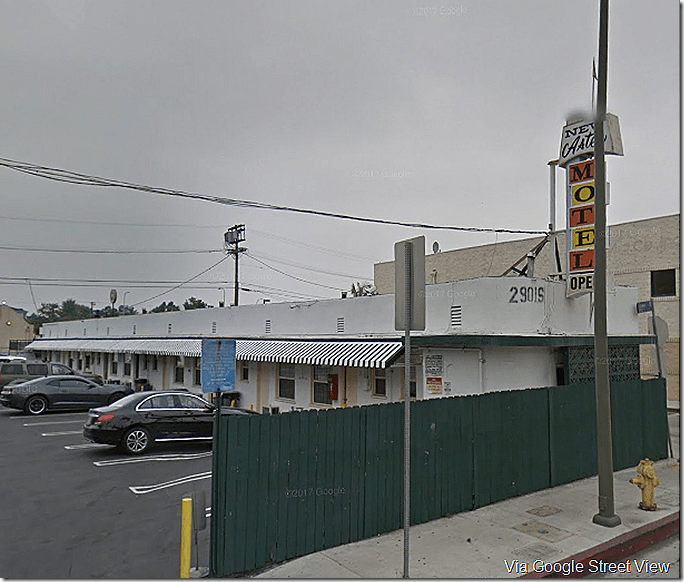

Perhaps most spell-binding is the description of Room 3 of the Aster Motel at the corner of Flower and Twenty-Ninth in Los Angeles. In an effort to investigate all the places that Leslie Dillon had lived, police came to learn that Dillon had spent time at the motel made up of ten concrete cabins and so officers went to the Aster and interviewed the owner. Amazingly, the proprietor reported that two years previous on the morning of January 15th, 1947, he had came upon one of the vacant rooms that was covered in blood and fecal matter. The room was in such a state that the owner cleaned it up himself keeping the maids and his wife out for fear they’d be sick. The sheets were so saturated with blood they had to be soaked before being sent out to the laundry. Additionally, the owner reported seeing a distinct footprint left in the blood on the floor. The owner’s wife and the maid confirmed the atrocious mess and added that there was also a bundle of men’s and women’s blood-splattered clothes that had been left behind. If there ever was evidence that a crime had been committed this was it and yet the owners of the Aster never reported it to the police. They had had trouble with the cops in the past and they didn’t want anymore.

In all, the investigation of the Aster Motel revealed that one of the rooms had been covered in blood on the very day Elizabeth Short’s body was found, that during the last week of her life a dark-haired girl had been seen staying at the Aster, that this same girl had been seen incapacitated, lying naked on a bed, that a bloody pile of women’s clothes had been discovered and discarded, that Leslie Dillon had spent time there in early 1947 and that a man matching Mark Hansen’s description had been seen there at the same time. Despite all this, the officers investigating this angle were abruptly reassigned and the Aster Motel investigation was dropped. Unbelievable.

It is perhaps no surprise that the author presents her case as irrefutable and after reading the book you are inclined to agree. But what is frustrating in a case like this is a perusal of the internet once you’ve closed this book presents many rebuttals and some outright dismissals of Eatwell’s claims. But, if you’ve just finished the book, the reader has no choice but to conclude that, if all the evidence she presents in Black Dahlia, Red Rose is true, then how can she be said to be wrong? A perfect example of this frustration can be seen when one investigates Dr. George Hodel. Eatwell concedes that the Hollywood gynaecologist and abortionist was a suspect in the Black Dahlia investigation but she dismisses out of hand the possibility that he was the killer. Yet the entire Hodel family, lead by Steve Hodel, George’s son and a former LAPD detective, insist that George Hodel killed the Dahlia. At the same time I was finishing Black Dahlia, Red Rose, I was listening again to the riveting podcast Root of Evil hosted by Hodel’s descendants. The case they lay out over the 8 episodes is absolutely spellbinding and – just as believable as the case Piu Eatwell lays out for the murderer having been Leslie Dillon. I suppose it is inherent in the investigation of unsolved crimes that conjecture abounds and more than one hypothesis can sound iron clad, completely believable and logically sound.

Through this book I learned about Hollywood madam Brenda Allen and how her relationship with police rocked the LAPD exposing rampant corruption in the police force. I first learned here of the existence of such a thing as a grand jury and what their responsibilities are. In the case of the Black Dahlia, one grand jury found that there is “something radically wrong with the present system of apprehending the guilty” and noted that there seemed to be “corrupt practices” employed by many police officers. This jury’s tenure was up, though, and nothing ever became of their recommendations. Eatwell makes note of Curtis Hanson’s spectacular 1997 film that looks at this era in the LAPD but she refers to it as Hollywood Confidential as opposed to L.A. Confidential. She mentions that real life police chiefs and LA mayors are depicted in the video game L.A. Noire and this may have been the first I ever heard of this game that has become a years-long obsession with me. And in the final pages Eatwell makes a startlingly salient point. She notes that Leslie Dillon concealed evil behind a bland and innocuous facade. In an era when those who appeared “different” were often suspect, he was overlooked as too ordinary. So the investigation withered and died in part because there was no “Other” to blame; no homosexuals, no Chinese, Communists or Mexicans. The murder of Elizabeth Short and the way the investigation was carried out brought into horrific relief that, in post-war America, the darkness often came from within.

Eatwell’s book leaves little doubt that the murder of Elizabeth Short happened to take place at a time when corruption was rife at the LAPD and this most colossal of cases was bungled and/or steered away from completion because of the rot in the largest police force in the country and because of the culpability of many detectives. It’s also clear that in the late 1940s shady players in Hollywood operated in the dark shadows in which little lost girls like Beth Short were floundering, searching vainly for a happy ending. And these same villains were enmeshed with the police department.