I’ve always read a lot and a lot of it has been about music. As an obvious and direct result of this I have always known about more albums than I have actually heard. Think of the Beach Boys 40 years ago. Many books I read talked about the unreleased SMiLE album and so I knew of those songs long before I ever heard them. I recall sitting in the library of my high school and reading one of the editions of Rolling Stone Magazine’s best albums of all-time books. When I saw that an album was considered one of the best ever and when I read the editor’s take on the album I was oftentimes intrigued and excited to listen to the album and hopefully get from it myself what so many others had gleaned. Now, sometimes this resulted in severe disappointment but that, perhaps, is a discussion for another day.

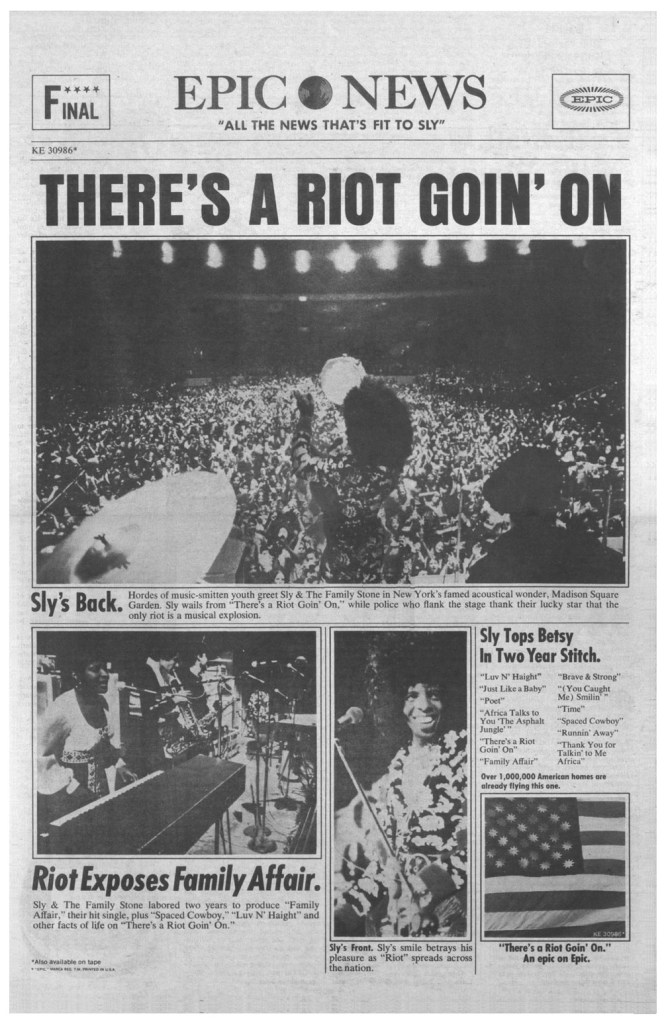

A companion to this discourse is notable moments in rock history that are less obvious and not easily assimilated or understood. Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock & Roll” is a glorious no-brainer but Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain” may require more explanation and challenge the listener to get hip to what is being put down. In other words, some of the greatest music of all-time needs to be explored and explained on many different levels for the listener to really understand what has been achieved. Perhaps one of the best examples of this is the record we’re talking about today, Sly and the Family Stone’s 1971 album There’s a Riot Goin’ On from Epic Records.

This is one of those records I had heard about and wanted to own quite badly. First because I love Sly Stone and his outfit and secondly because the record has often been described as seminal and one that was a signpost of sorts, a statement. So, I bought it during the brief time I spent buying music from iTunes and I listened to it but more in passing and so therefore I could not hear what all the fuss was about. I learned, though, that like a lot of albums – and a lot of other things, really – this was a record I had to really sit and listen to in order to get everything that had been put into it out of it. I also kept in mind having read Greil Marcus’ book Mystery Train in which he talked some about Sly Stone’s lyrics and when he referenced them from songs I knew they were mostly new to me. This concerned me; shouldn’t I know what Sly was singing about and not just digging the stone groove he was laying down? Sure, I should.

Enter my two sons. They know their old dad well and one of them for Father’s Day bought me this album brand new and on red vinyl and it waited in my Up Next section until I could get to it. Then it waited some more because I knew I needed to clear a block of time and really dig in to it. Eight months later I cleared a Saturday afternoon when I was alone in the house to listen and this was some months after I had gained Stone’s own perspective on the record by reading his memoir, Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin).

And now it’s time for another episode of Artist vs. Record Company. The Family Stone’s fourth album, Stand!, was released in May of 1969. It is still considered the band’s finest moment and a significant album of the 1960s, selling three million copies and spawning hits like “I Want to Take You Higher”. And despite admonitions like “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey”, the record is marked by optimism, declaring “You Can Make It If You Try” and calling for togetherness with the Number One song “Everyday People”. Later that summer, the band unleashed a performance for the ages and created an iconic moment of the Flower Power movement with their set at Woodstock, one of the two finest segments of the festival (Santana).

Mogul Clive Davis appears in the stories of many artists and at this point in time he was an executive at Columbia Records, parent label of Epic. He had hoped for new material from the band sometime early in 1970 but the Family Stone was struggling. First off, the Black Panther Party was pressuring Sly to align with them and to fire the band’s Jewish-American manager, Dave Kapralik, there was also much infighting between the band members and Sly Stone’s behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic. Added to all this was Sly’s and the band’s increased usage of drugs; and not mellowing marijuana or “happy smoke” but much heavier chemicals like cocaine and PCP. And Sly was surrounding himself with gangster bodyguards and Mafiosos who he had handling his business and finding him drugs. The band wasn’t offering any new music for the label to release and 1970 saw only the record company-generated Greatest Hits and the all-world single, “Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin)”, a song who’s lyrics hinted at darker goings-on.

But Stone was starting to make music again, mostly in his home studio, but drug use and his perception of what was going on around him was colouring his mood and this was borne out in the music that was taking shape. Stone could play any instrument and his discovery of a prototypical drum machine, the primitive but effective Maestro Rhythm King MRK2 with its preset beats, allowed him to work on the record alone. In his memoir, Stone says he would leave parties in his home and go up to his bedroom loft and lay down vocals which he would often do laying down in bed. Sly’s manipulation of the drum machine and his extensive overdubbing lead to a “dense mix” and a “muddy, gritty sound”. It was noted after this music was released that this results in the listener not being able to make out the lyrics which inhibits comprehension of what Sly is trying to get across through his words. For me, it also results in a fluid record that almost sounds like 12 movements of one single piece of music. Difficult then, to break down the record but let’s try.

After all this talk of drum machines, it’s worth noting that the record begins with some actual drums and I’m hoping that’s Sly and the Family Stone’s drummer, Greg Errico, we hear getting the first track, “Luv N’ Haight”, under way accompanied by some funky wah-wah guitar. And right out of this Haight gate we hear something else that marks the record and that is Sly Stone’s insistence on delivering the lyrics in what amounts to a mumble as if he is so down with the flow that enunciation would be a buzzkill. Interesting, too, that the lyrics of “Luv N’ Haight” you can hold in your fist; “feels so good inside myself, don’t want to move” and that’s about it. But no matter – if this record is about the groove then we’re off to a good start.

Track two, “Just Like a Baby” introduces us to the stellar keyboard sound used throughout the album. Sly used synthesizers and keyboard programming and he either uses my favourite instrument, the clavinet, or replicates it on synth. Speaking of keys, Sly turned to some special guests he utilized in place of the Family Stone, people like keyboardist Billy Preston, Bobby Womack and Ike Turner. This track also brings the meandering funk trance vibe that permeates the record. Now, “Poet” – shut the front door. A dearth of words talking about writing songs but this one’s all about the keys, man, dig that.

The record company must’ve been thrilled by “Family Affair”; “I hear a single!”. A percolating groove roils beneath the “it’s a family affair” repeated line that invites you to sing along. That’s Billy Preston on keys and Sly elevates his vocal to intelligible levels but its still imbued with that casual lethargy. “Family Affair”, though it came from this challenging album, was Sly and the Family Stone’s most successful single reaching Number One on both the Pop charts (for 3 weeks) and R&B listings (5 weeks).

Stone’s MRK2 starts off the 9-minute “Africa Talks to You ‘The Asphalt Jungle'”, a song that was originally the album’s title track. It’s another eyes-closed, head-bobbin’ work-out but it is an example of Sly hiding behind some wordplay and emitting stanza’s that are inscrutable at best, nonsensical at worst. Here he gives out with “Must be a rush for me to see a lazy. A brain he meant to be. Cop out? He’s crazy!”. Say, what now? And, yes, “There’s a Riot Goin’ On” is Track 6 but it is zero seconds of silence, timed at 4 seconds on the compact disc. Sly explained the Side One closer by saying that “there should be no riots”. He would add in his memoir “that was a message, too-don’t give any time to violence. Don’t give it the time of day. There’s a runout going on”.

Side Two starts off with the drum machine again and Sly’s vocal on “Brave & Strong” sounds like its coming from another room. The tune is a call to arms of sort, encouraging the listener to “Survive! Survive!” but throws in some more bonkers lyrics; “Before me was a Cowboy star. Indians! And there you are”. Both this tune and the next, “(You Caught Me) Smilin'”, shuck and jive along nicely with the latter utilizing some brass. It was the third single from the record and just fell short of the Top 40. “Time” is a slow-moving tune that is heavy on the keys and features some impassioned soul singing from Sly. “Spaced Cowboy” features more muddled vocalizing – until Sly starts yodeling. This incongruous sound gives the listener a bemused grin and serves as a bit of an oasis. Likewise is the pleasant, shuffling “Runnin’ Away”, another single from the record and one that reached Number 23 US Pop. This tune’s production sounds much cleaner making it stand out somewhat from many of the other tunes.

The record ends with “Thank You for Talkin’ to Me, Africa”, a slowed-down revisiting of the band’s previous hit single, “Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin)”. Over a prominent bass line, Sly mumbles the words that, more than any other song on the album, express the violent realities of the day. This funk trance goes on for over 7 minutes with Stone’s mumbles punctuated with screams and moans and blasts into the brief choruses.

Not surprisingly, the record was met with some indifference as it was just too hard to latch on to. Critics and listeners were definitely challenged but that didn’t stop There’s a Riot Goin’ On from reaching Number One on the Pop charts and the Top Soul Albums chart. Then there were the two Top 40 singles including the Number One “Family Affair”. The record caused reviewers to pull out all the stops. Rolling Stone called it “new urban music” and said “it’s about disintegration, getting f*cked up, nodding, maybe dying. There are flashes of euphoria, ironic laughter, even some bright stretches but mostly it’s just junkie death”. Others noted its “ghetto pessimism” and “jarring song compositions”.

The album was going to be called Africa Talks to You “The Asphalt Jungle” until Marvin Gaye released What’s Goin’ On which prompted Sly Stone to respond. And herein lies this record’s appeal for me and partly what makes it so striking and worthy of discussion. In many ways, it was the “anti-record” and was akin to a performer standing on stage with his back to the audience. It was Sly gathering his people and telling them that things ain’t that great. In “Family Affair”, Sly sings of the struggles facing newlyweds. It ain’t all about romance and while navigating this new relationship you can end up “cryin’ anyway ’cause you’re all broke down!” and in “Africa Talks to You” it’s “timber…all fall down” and “watch out, ’cause the summer gets cold”. Later there is talk of “frightened faces to the wall” and “Thank You” speaks harshly:

“Lookin’ at the devil, Grinnin’ at his gun. Fingers start shakin’, I begin to run. Bullets start chasin’…Thank you for the party, I could never stay…Flamin’ eyes of people fear, Burning into you. Many men are missin’ much, Hatin’ what they do…Dyin’ young is hard to take, Sellin’ out is harder.”

While the sentiments aren’t all grim, the record plays like a 47-minute greeting card of doom. If it wasn’t so dang funky it might be a real bummer trip. Sly Stone knew that much of youthful society was beginning to turn away from the optimism of the civil rights movement, anti-war protests and Flower Power in general and he wanted to make a record that spoke some street truth. Marvin’s record is venerated today as a peaceful treatise and rightfully so but Stone’s message and its presentation were tougher to swallow and much less accessible.

With his mush mouth vocalizing and the production a blurry smudge, I can’t help but think that Sly Stone was intentionally being unintelligible as a way of pointing to the unrest of the time. Here’s two Black men with varying reactions to how things were in the world and for their people and for all people. Gaye seemed sad and resigned; Sly was pissed and combative. Stone was telling the audience that he saw things differently. To my ears, Marvin’s record was peace, love and MLK while Sly’s was more peevish, more Malcolm X. Marvin was Sidney Poitier, Sly was Jim Brown. Marvin was proselytizing and protesting, too but in a much gentler way with sounds – though angelic – that were subservient to AM radio airplay. Marvin Gaye was exasperated. He threw up his hands, shook his head sadly and asked “what’s going on?”. Cynical Sly smirked, snorted and replied “there’s a riot goin’ on!”.

This album is considered one of the first instances of true, pure funk music and it also aided jazz artists like Herbie Hancock and Miles Davis in their explorations of fusion. Many reviewers discerned at once what Stone had done and referenced the record’s harshly realistic look at the times in which it was released, it’s unflinching disillusionment. Many said, though it was somewhat unsettling and difficult to listen to, the results were undoubtedly stunning. It is perhaps the most impenetrable of all the masterpieces created in the original rock era.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On (KE 30986 – 1971) – from Epic Records

Produced by Sly Stone

Side One: “Luv N’ Haight”, “Just Like a Baby”, “Poet”, “Family Affair”, “Africa Talks to You ‘The Asphalt Jungle’”, “There’s a Riot Goin’ On”

Side Two: “Brave & Strong”, “(You Caught Me) Smilin’”, “Time”, “Spaced Cowboy”, “Runnin’ Away”, “Thank You for Talkin’ to Me Africa”

Sly Stone – vocals, drums, drum programming, keyboard programming, synthesizers, guitars, bass, keyboards // Rose Stone – vocals, keyboards // Billy Preston – keyboards // Jerry Martini – tenor saxophone // Cynthia Robinson – trumpet // Freddie Stone – guitar // Ike Turner – guitar // Bobby Womack – guitar // Larry Graham – bass, backing vocals // Greg Errico – drums // Gerry Gibson – drums // Little Sister – backing vocals

Recorded at The Record Plant, Sausalito, California and Sly Stone’s home studio, Bel Air, California