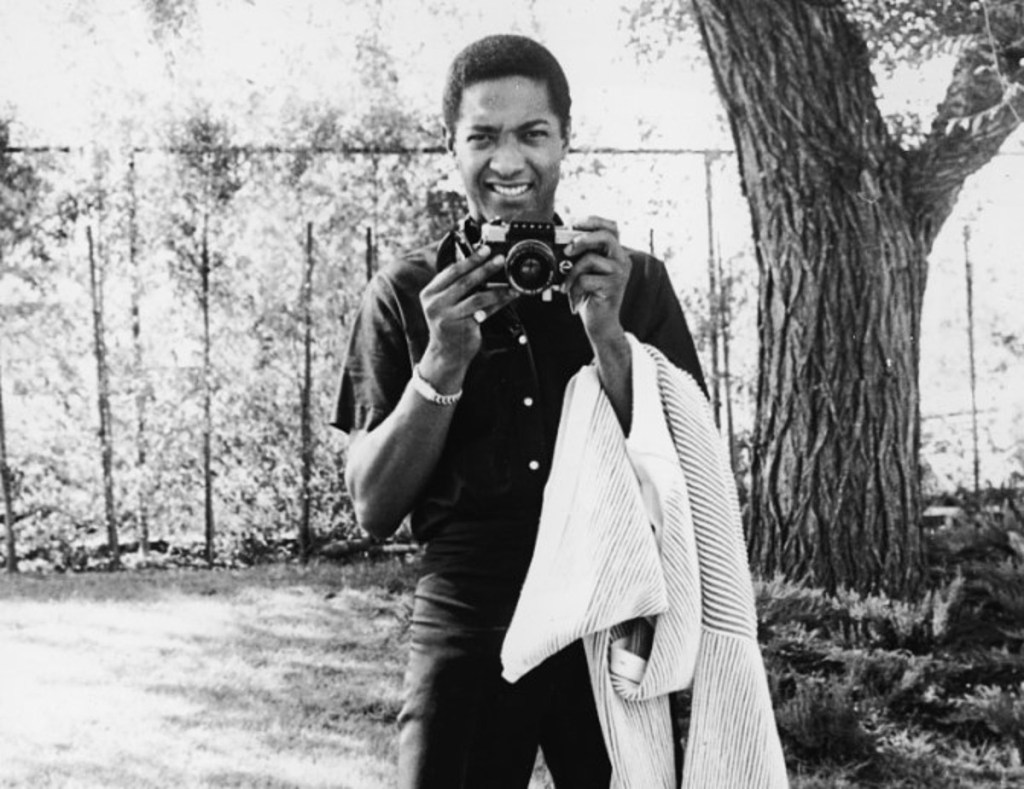

Sam Cooke is a truly legendary performer who perhaps does not get his due. Seemingly lacking the strong virility of Otis Redding and perhaps not having the innovative, music-making reputation of Marvin Gaye, Cooke’s contributions are maybe not heralded enough and his music not pored over as much as it should be. These three men, though, are connected not only by their strong vocal legacies but also by their tragic ends.

Sam was born Sam Cook in Mississippi in 1931. He was the son of a minister and, like many of his contemporaries, he started his career as a gospel singer. When Sam was 14, he joined a gospel group called The Highway Q.C.’s. Perhaps unknown today, this group is still operating, having been in existence for over seventy years. In 1951, Sam left the Q.C.’s (and was replaced by Lou Rawls) to join the Soul Stirrers, a pioneering gospel quartet that had already been popular for 30 years and a group that had brought many innovations to quartet singing. Sam was 20 when his first song with the Soul Stirrers, “Jesus Gave Me Water”, became a hit on Specialty Records. While gospel quartet singing was popular at the time, Cooke is said to have brought added attention to it and he put a handsome, dynamic face on the genre. Sam and the Stirrers recorded many songs together, including “Peace in the Valley”, before Cooke left in 1957. The Soul Stirrers remained vibrant for a short time after with Cooke’s replacement, Johnnie Taylor (later of “Who’s Making Love” fame).

Cooke’s first secular single was released under the name “Dale Cook”; the alias was used in order not to alienate the fans of his gospel music as there was at the time a stigma against gospel singers recording popular music and vice versa. Specialty Records was pushing Cooke to make records that sounded like those of the label’s top artist, Little Richard, a move that Cooke was not interested in. Sam commiserated with his preacher father who gave him his blessing to record secular music. Sam then left Specialty and added an “e” to his last name, declaring it a new start.

Moving to the brand new Keen Records, Sam began a recording career that was one of the most successful of the golden era of 1954-1963. He also began making records that were somewhere between rhythm and blues and pop. He got off to a great start with “You Send Me”, a song written solely by Cooke, giving an early indication that Sam would be able to not only record but compose songs and thereby have a measure of control over his career. The song was a smash hit, reaching #1 on both the pop and R&B charts. Teresa Brewer tried to capitalize by quickly releasing a cover version that went to #8 Pop. Sam’s recording of “You Send Me” has gone down in history as a significant song of the early days of the genre that Cooke was creating almost single-handedly; soul music. The song features on lists of the “most important” and “greatest” songs ever recorded (#115 on Rolling Stone‘s list of the 500 greatest songs).

Courtesy Motown Today YouTube channel.

Also in 1957, Sam released “(I Love You For) Sentimental Reasons”, a song that landed in the Top 20 and while his next several records featured in pop’s Top 40 and ranked in the Top Ten of the R&B charts, he had to wait until 1959 to release numbers we all cherish today. Early that year, his “Everybody Loves to Cha Cha Cha” (#31 Pop, #2 R&B) and “Only Sixteen” (#28 Pop, #13 R&B) were released and received much airplay. Interestingly, many of Sam’s early records charted well but somehow they are not heard much today. Songs like “I’ll Come Running Back to You” that reached #18 Pop while topping the R&B listings and “Lonely Island” that was written by Eden Ahbez and peaked at #26 Pop. “Win Your Love for Me” hit #22 in 1958 but is basically unheard and unknown today.

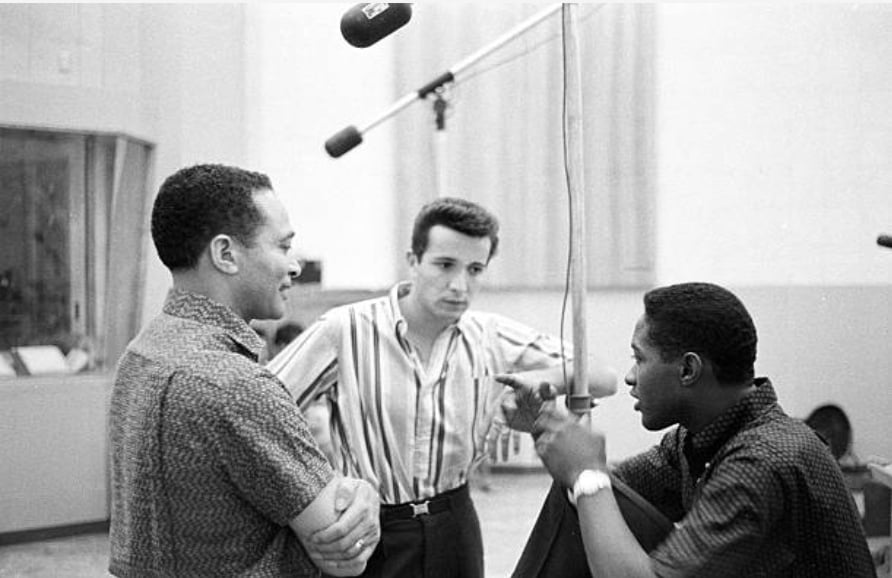

Sam moved to RCA Records in 1960 but it was an old song he had recorded while still at Keen that provided him with his biggest hit since “You Send Me”. At an informal – and, in fact, his final – recording session for Keen, Cooke worked with the fledgling songwriting team of Lou Adler and Herb Alpert. The duo had written what Adler felt was a trite song about love trumping such things as knowledge and education. Cooke insisted the tune had merit and he tweaked the lyrics to punch up the education aspect of the song. “Wonderful World” featured an arrangement by Belford Hendricks, who would perform a similar duty on many of Sam’s biggest hits. Hendricks would go on to earn some scorn for his work with Nat Cole on that singer’s country and western-flavoured later albums. “Wonderful World” was released on Keen Records in the spring of ’60 in direct competition with Sam’s current singles for RCA and would reach #12 Pop. Historically, “Wonderful World” is one of the many songs of Sam Cooke’s that have endured through the years to be covered many times and featured often in films and other media. It also serves to accentuate the assertion that Herb Alpert‘s contributions to popular music are significant, far-reaching and unique.

For the next few years, Sam would release songs that landed in the upper reaches of the charts and that have gone down as some of the finest recordings of the era. In 1960, “Chain Gang” reached #2 on both the Pop and R&B charts while “Sad Mood” featured in the Top 30. 1961’s “Cupid” was another hit for Sam and is perhaps his most pleasant pop song. 1962 was a good year for Cooke as he placed four songs in the Top 20. “Bring It on Home to Me” is a stunning ballad that features Sam’s old buddy, Lou Rawls, singing the second lead and “Having a Party” was a fun song that hit #17 Pop #4 R&B. Early in 1963, Sam enjoyed one of his biggest hits when “Another Saturday Night” peaked at #2 on the R&B listings and was a Top 10 pop song.

© RCA/Legacy

There was much more to Sam Cooke than just chart success, though. In 1961, Sam started SAR Records, intended as a means by which Cooke could discover, record, nurture and promote various African-American singers and this record company was one of the ways that Cooke began to fight for racial equality in the turbulent early 1960’s. In addition to this, though, was SAR’s practice of putting the needs of the artist first and foremost. Up until this point in popular music, it was the people behind the artist who seemed to benefit the most from a singer’s work. This was not the case at SAR. Cooke himself had felt pressured by record companies to be something he was not and so he started a practice of working with the artists to let their true talents emerge. This way of doing business did not sit well with other record labels who saw this as the emergence of a trend elevating the importance of the artist and thereby eventually undermining their power.

“Sam was the one who started the black guys to wearing ‘fros. Before that, our hair was processed…switched over immediately. All the black guys started gettin’ the ‘fros, y’know? Sam was a powerful man.”

– Smokey Robinson

Sam Cooke also came to the attention of the FBI. In the early 1960’s, Sam formed friendships with powerful men in the civil rights movement. At this time, Malcolm X was a controversial activist who was an adherent of the Nation of Islam and who advocated for black supremacy and the separation of blacks and whites. A recent convert and close ally of Malcolm X was boxer Cassius Clay who took the name Muhammad Ali when he joined Islam. These two – along with athlete and actor Jim Brown – befriended Cooke and the four became a tight-knit alliance. According to many, Cooke had no interest in joining Islam but he cherished the association with these men and it was one that could be considered a huge threat to the balance of race relations in America at the time. Four powerful, charismatic, handsome, accomplished black men from different public arenas banding together created a force that could have affected great change, particularly in the way young black people saw themselves and their potential futures. Indeed, the concept of “Black Power” could legitimately be traced back to this quartet of men. Jim Brown says that the four of them would meet and talk about their dissatisfaction with second-class citizen status and about their determination to stand up for their rights.

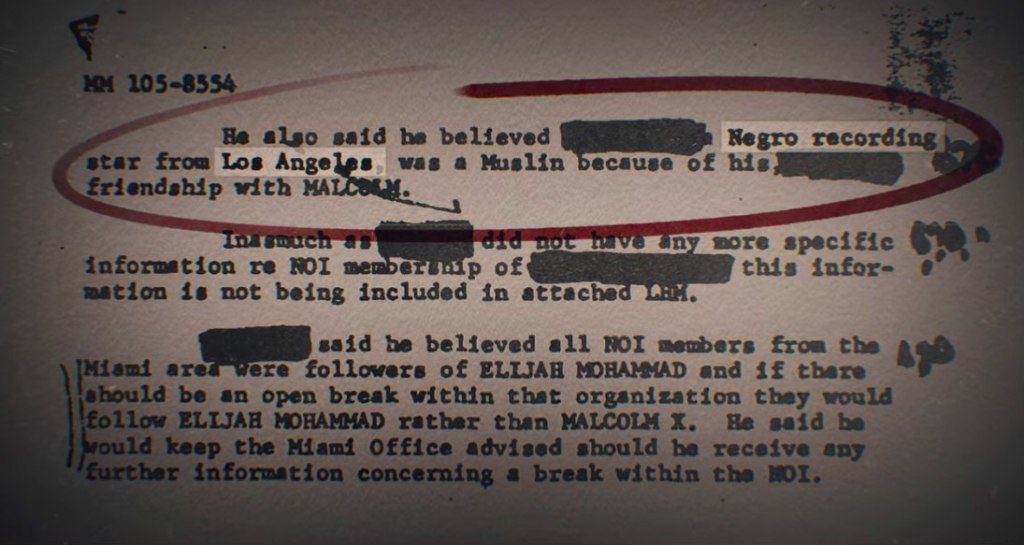

Informants began to emerge everywhere supplying information to the government on who was meeting with who and talking about what. Malcolm X and Ali were watched closely by the FBI and Sam’s name – “Negro recording star”, actually – began to show up in documents. It began to dawn on many that perhaps Sam was the biggest threat of the four as he was already in white living rooms. RCA was also beginning to be concerned with the radicalization of their big star. The newspapers and trade papers began to notice and report on Sam’s fights against segregation, particularly in his audiences at concerts in the south.

On December 11, 1964, Sam Cooke was shot dead at the Hacienda Motel at 9137 South Figueroa in Los Angeles. The night had started rather joyously with dinner at the popular Martoni’s Restaurant at 1538 North Cahuenga. Sam had been to his bank to withdraw $5000 from a safe deposit box; recording engineer and friend Al Schmitt remembers Sam flashing $1000 at the restaurant. What happened when Sam left Martoni’s has gone down in the public record but was immediately disputed and continues to be shrouded in mystery today.

Sam left Martoni’s with Elisa Boyer, a young woman he had met at the restaurant and the two went to the Hacienda, a well-known hang-out for hookers that offered rooms for $3 an hour. The official report states that, once in a room, Sam became violent with Boyer and that she began to fear for her life. When Sam went into the bathroom, Boyer took the opportunity to escape. She grabbed a pile of clothes and ran. When Cooke found her gone, he became enraged. He realized that Boyer had taken his clothes as well as her own and he went looking for the young woman dressed in only a sport coat and one shoe.

Cooke, inebriated and angered, began to pound on the motel’s office door, shouting “Where’s the girl?!”. The night manager, Bertha Franklin, told him she was alone and refused Sam admittance but Sam eventually broke the door down. The two struggled and Franklin grabbed a gun and shot Cooke in the chest. Bewildered, Sam exclaimed “Lady, you shot me” and gradually slumped to the floor against the door jamb. When Sam had begun knocking on the door, Franklin had telephoned the motel’s owner, Evelyn Carr. The phone had been laid down and Carr had heard everything. She called the police saying “I think she shot him”.

What was told to the police and what emerged at the coroner’s inquest flew in the face of everything that anybody who knew Sam thought possible. Fellow diners at Martoni’s seemed to feel that Boyer had latched onto Sam and had left with him willingly. At the inquest, Cooke’s lawyers were given the chance to ask but one solitary question of the three ladies who testified, Boyer, Franklin and Carr. Tests showed that Sam Cooke was drunk at the time of his death and the testimonies of the three women corroborated each other. Therefore, the coroner’s jury had no choice but to render a verdict of justifiable homicide.

No one who knew Sam Cooke believed that things went down as described at the inquest. Friends said that Cooke was too classy to take a girl – who many thought was basically a prostitute – to a $3-an-hour motel and that he was not the type to become violent and take a woman by force; he simply never had to. Unfortunately, other friends were perhaps more honest. Tellingly, Sam’s mentor and producer “Bumps” Blackwell once said “Sam would walk past a good girl to get to a hooker” and Sam had a reputation as a womanizer. One theory is obviously that Sam Cooke was played for a chump. Boyer spotted him at Martoni’s and knew who he was; and if Sam was flashing a roll, that made him a more attractive mark. Once at the motel, Boyer saw her chance and absconded with Cooke’s clothes and money – the $5000 Cooke was said to have had that night was never found. Embarrassed and enraged, Cooke went looking for the girl and met his fate.

In the aftermath, Bertha Franklin – the woman who shot Sam Cooke – received numerous death threats and had to go into hiding. She resurfaced, though, to sue Cooke’s estate “citing mental anguish and physical injuries”. Perhaps disgusted, Cooke’s widow, Barbara, countersued. However, Franklin – the woman who shot Sam Cooke – was awarded $30,000. Franklin relocated to Michigan and died in 1989. Elisa Boyer – who had testified in support of Franklin’s lawsuit – was arrested for prostitution exactly one month after Cooke’s death. She was again arrested in 1979 after a fight with her boyfriend that lead to his death. For this, she was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years-to-life.

A deeper conspiracy theory surrounding Cooke’s death concerns his rise as a powerful black man and a threat to record companies across the country. Cooke had never been shy about fighting for equality. He refused to play to segregated audiences and was a very visible champion of black artists. His association with Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali brought Sam to the attention of the FBI. With the suggestion at the time that civil rights were akin to Communism, the white American establishment may have been afraid of Sam, a popular entertainer beloved by all, including middle-class whites. Some may have felt that he needed to be silenced. I’m going to be naive and say that this seems implausible. At the same time, however, it may not be hard to believe that Sam raised concerns in the halls of power. Consider that Malcolm X was shot dead in February of 1965, a mere 9 weeks after Sam was killed.

“‘In the course of the two or three hundred different interviews with different people that I did for the book, there are two or three hundred different conspiracy theories,’ he said. ‘While they were all extremely interesting, and while every one of them reflected a basic truth about prejudice in America in 1964 and the truth of the prejudice that has continued into the present day, none of them came accompanied by any evidence beyond that metaphorical truth.'”

The above quote is from scholar Peter Guralnick, author of the definitive biography of Elvis Presley and also of the Cooke bio Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke. I take Guralnick’s words to mean that it is impossible to prove a conspiracy in the death of Cooke. I believe it further means that there is a strong chance that white America was successful once again in silencing a black voice and thereby scoring another triumph over the rise of racial justice in the 1960’s.

“He was Berry Gordy before Berry Gordy.”

– legendary record executive Lou Adler referring to Sam and SAR Records.

By the numbers, Sam Cooke ranks up there with the biggest recording stars of the golden era of 1954-1963. Between 1957 and 1964, Sam had one #1 song, 5 Top Tens and he placed 28 records in the Top 40, charting a total of 41 singles. But there is so much more than numbers to the career of Sam Cooke. I have always considered Sam the very first hit-making singer of soul music, a genre he may not have created but one that he did much to popularize. The intangible delight of his number one smash “You Send Me” often leaves one at a loss to describe it. It sounds unique enough from other records of the time that a new appellation was needed to describe the sound; soul. It’s this writer’s opinion that the origins of soul music can be found only in the records of Sam Cooke and Ray Charles.

As a songwriter, Sam was able to take what he saw around him – everyday life situations – and make them into catchy, exciting songs that many could relate to. Often in an instant, out of thin air. While with the Soul Stirrers, a new song was needed for an engagement while the group was en route. Sam asked for a Bible and, flipping the pages and landing at Matthew 9:20, came up with “Touch the Hem of His Garment” on the way to the show. At a party at his home, one of his children excitedly admonished the adults to get up and dance; “everybody cha cha!”. It was not long before Sam grabbed his guitar and wrote “Everybody Loves to Cha Cha Cha”. While driving with his entourage through the rural south, Sam and company passed a group of prisoners working on the side of the road. Turning around, Sam asked the officers in charge if they could give the men Cokes. After providing these road workers with a welcomed break, Sam got back in the car greatly touched by those he met. He sat in the backseat and wrote “Chain Gang”. Sitting in his living room watching TV, Sam saw reports on the action at New York’s Peppermint Lounge where the Twist was all the rage. That night, from his pen flowed “Twistin’ the Night Away”. On a 1963 tour of England, Cooke and his gang were staying at a hotel where women guests were not allowed. Everybody was down until Sam started noodling and in no time he had composed “Another Saturday Night”.

When Sam was the new lead singer of the Soul Stirrers, he attempted to emulate the vocal sound of his predecessor but couldn’t match it. In trying to do so, he ended up with a trademark flutter in his voice that he would ever after employ to express joys and sorrows in happy songs and sad ballads. For the true sound of soul singing at its origin, listen carefully to Sam’s “Good Times”, “Just For You” and particularly “Bring It On Home to Me”, a record that has been described as “perhaps the first record to define the soul experience”. However, Cooke’s most lasting contribution to music may be his stunning “A Change is Gonna Come”. Exasperated by prejudice and “embarrassed” that only the white Bob Dylan was recording songs making such comments, Cooke composed this song that he himself considered “ominous” but one that was the most complex of his many compositions. In December of ’64, when the song was being prepared for single release, RCA wavered and actually deleted a line from the song, deeming it too controversial; “I go to the movie and I go downtown. Somebody keep tellin’ me ‘don’t hang around'”. The song was released two weeks after Sam Cooke was shot and immediately was embraced by the civil rights movement. It tells “the story of both a generation and a people”.

The ramifications of Sam Cooke’s sad death should not overshadow the glory of his voice and the sparkling records he left us.

“Sam Cooke’s yours. He’ll never grow old.”

© Universal Music Group

Ten from Cooke

- You Send Me

- Only Sixteen

- Sad Mood

- Cupid

- (What a) Wonderful World

- Chain Gang

- Bring It On Home to Me

- Another Saturday Night

- Having a Party

- A Change is Gonna Come

Sam Cooke was a known womanizer. He was married at the time of his death but he had multiple children out of wedlock. He should have never gone to that motel with a prostitute. I believe the woman tried to rob him after he undressed which could explain why he chased her. A sad ending to a talented crooner’s life.

You are bang on right. I admit I avoided stating bluntly that if you avoid putting your head in the noose, you don’t get hung and if you play with fire, you get burned, etc. Sam made some bad choices, as we all have, and it did indeed lead to a sad end. Thanks for your comment.