I have long wanted to write an article on sequels. I am always fascinated by what can “happen” when a sequel is released or a film is remade. The results can range from magnificent (Death Wish 3) to abysmal (Another 9 1/2 Weeks).

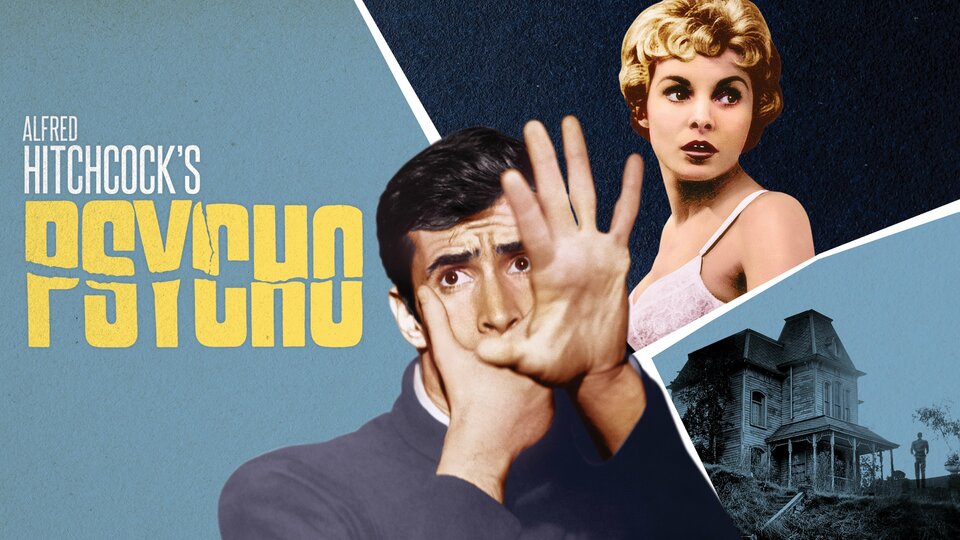

Some films, we may all agree, should never be remade or have inferior sequels attached to their legacy like so many ugly barnacles stuck to the bottom of a pristine vessel. One of the films likely on many movie fan’s list of “Do Not Touch” would be Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 psychological horror film Psycho. This movie is the very definition of “classic” and “has become one of the most recognizable films in cinema history”. It’s shower scene “has become a pop culture touchstone and is often regarded as one of the most iconic moments in cinematic history, as well as the most suspenseful scene ever filmed”. So, it is on a very short list with other of the greatest films in history. But not only did it receive a sequel, it got three sequels. And not only did it receive three sequels but it was remade. Not only did it receive three sequels and a remake but there came much later an installment of the story in the form of a TV movie and if all that wasn’t enough you can add a television series. But – there’s more.

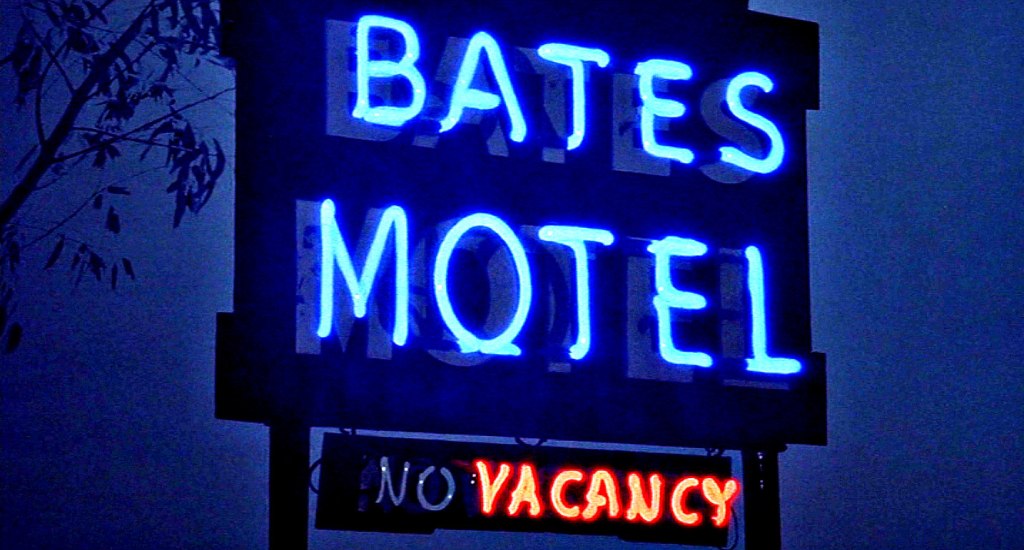

Psycho started life as a novel. Robert Bloch (1917-1994) published in 1959 the story of Norman Bates, a mild-mannered bachelor who lives with his domineering mother. The book tells basically the same story the film does. For the uninitiated, Norman and his mother run the decrepit Bates Motel. When a pretty blond woman arrives for the night having stolen money from her boss, she is attacked and killed by someone who looks like an old woman. When the dead blond’s sister and boyfriend come looking for her, the “old woman” kills again. Soon it is revealed that old Mrs. Bates has been dead for some time and her death caused poor Norman to have a nervous breakdown and he spent some time in a mental institution. In the end we learn that “Mrs. Bates” has been killing no one – it has been Norman dressing like his mother and assuming her identity.

Robert Bloch also wrote two sequel books that have no place in the Psycho cinematic universe. The aptly named Psycho II (1982) tells of Norman escaping the asylum and heading to Hollywood. In this book, Bates kills again – twice – but is, remarkably, killed himself and it is his psychiatrist who goes on a killing spree. Psycho House (1990) takes place ten years after Norman’s death and centres around the Bates Motel becoming a tourist attraction. Interesting to note that in these two stories it is others who do much of the killing. The sensitive nature of Norman Bates’ status as a crazed killer is something we will discuss later. It’s the films, though we are concerned with here.

In the original movie, Anthony Perkins portrays Norman with sensitivity and the right amount of susceptibility to madness. And while others have played Bates, it is Perkins who owns the character and over the years he has been able to portray Norman in such a way that he elicits sympathy and with a skill that allows the character to exhibit both a vulnerability and menace. The classic movie tale ends with Norman being declared psychotic and with his mother completely taking over his personality. This is 1960. Twenty-two years go by and Norman Bates is declared mentally sound and ready to re-enter society…

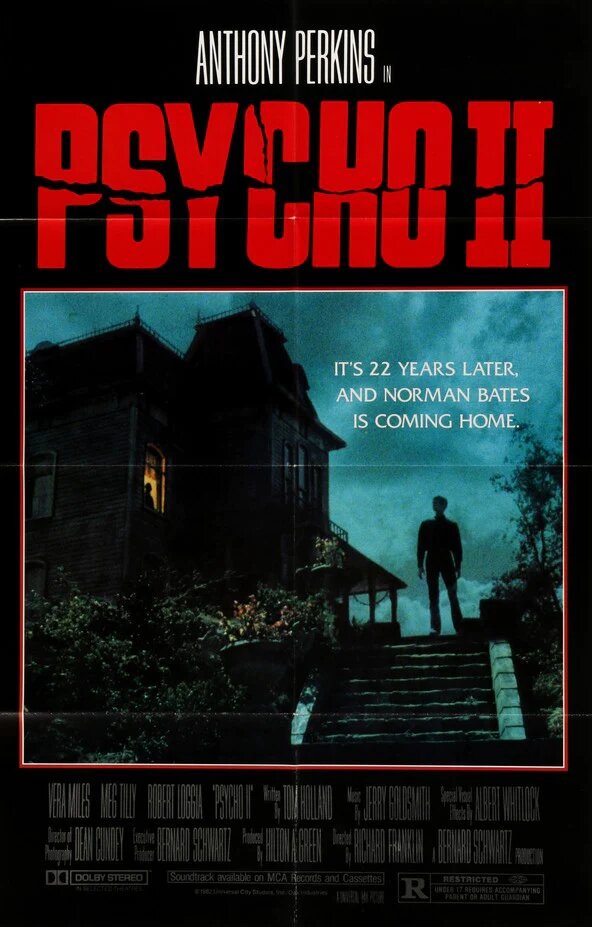

Psycho II (1983) // Directed by Richard Franklin and co-starring with Perkins are Vera Miles, Meg Tilly, Robert Loggia and Dennis Franz

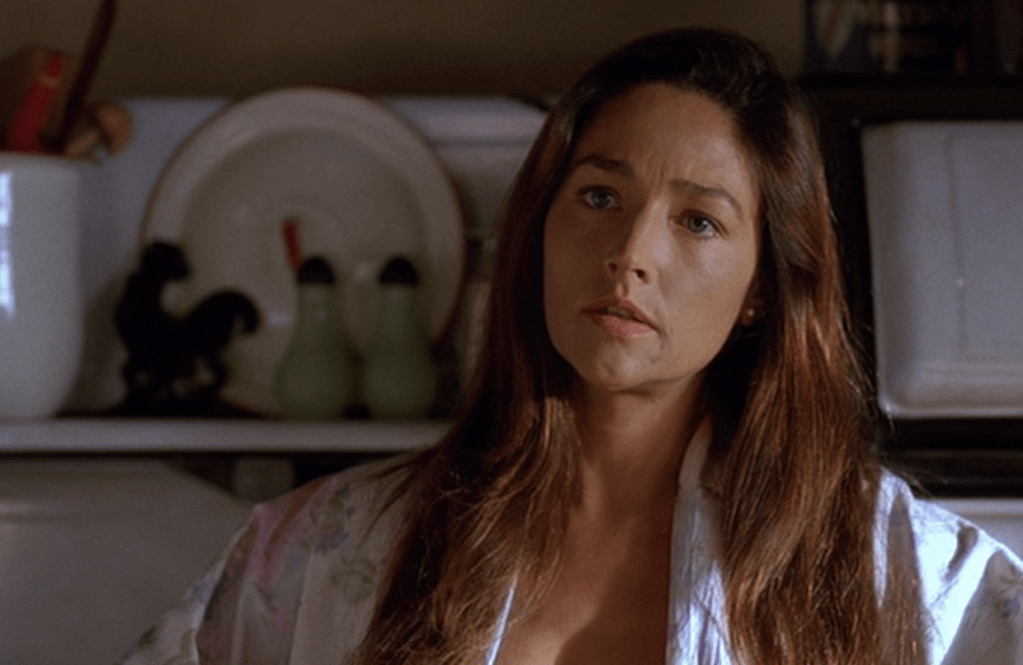

Norman Bates has served his time. He is about to be released from a mental institution and return to society. His doctor and friend Bill Raymond (Loggia) is pleased to see Norman free while Marion Crane’s sister is not. Lila Crane (Miles) is now Lila Loomis, having married her deceased sister’s boyfriend, Sam. Lila is livid that her sister’s killer is being released and she insists that he will kill again. Norman moves back into his old home next to the Bates Motel – and still hears his mother’s voice. He is set up with a job at a diner where his boss and waitress, Mary (Tilly) are kind to him. Not so kind is Warren Toomey (Franz), the lowlife who is now managing Bates Motel – and also dealing drugs from the office. Bates fires Toomey who retaliates by taunting Norman in public, calling him a “psycho”. Bodies start turning up and Lila Loomis uses this as proof that Norman is still of unsound mind and is back to his murdering ways.

I’m watching this movie and trying to reconcile its “slasher” rep with the poor Norman Bates I see on-screen. The unsettling final shot of the original film came to mind; Norman looking menacingly at the camera, a skull flickering into view. I was comparing that with the Norman of this second film and thoughts began to permeate. How on earth could Norman Bates go on being a killer? How could a studio green light a script depicting a person suffering from mental illness being a murderer? The answers are he couldn’t and they didn’t. Not really.

Norman’s two murders in the first film have been explained – poor guy was unstable. Now in the second film, he is passive, trying to get his life back and attempting to maintain his fragile sanity. It would have been untenable – almost cruel – to have Norman go on a rampage. That is simply not who he is and not a depiction of mental illness anyone wants to see. Then it occurred to me that these Psycho sequels are considered “horror” or “slasher” films yet it is not the main character who is the killer. Norman is not Jason Vorhees or Michael Myers or Freddy Krueger. Yet these Psycho films were promoted with images of Norman Bates looking murderous and they were able to release these films on the blood-splattered strength of the original classic.

The killing – for the most part – happens around Norman Bates in these sequels but it is Norman himself who is the victim. In this film, we see him scared, we see him flinch when he uses a knife to cut a sandwich, we see him victimized by Toomey but also by his memories. He is a victim of his mental instability. This puts the viewer on his side and makes us pull for him. Any killing Norman does is depicted as justifiable.

But I will say there is a clue at the very beginning of this film that I think confirms that Norman Bates is indeed a psycho. He wears his suit jacket with the BOTTOM button done up as opposed to the top. Obviously he’s not ready to re-enter civilized society.

The main things we need to know about this first sequel is that it was genius to cast Vera Miles as Lila Loomis and to have had her marry Sam. In the original film, Lila was a bold, strong character and she takes this attitude to extremes in the sequel. Secondly, the studio made an attempt to get Norman out from under his mother by giving him another. Psycho II introduces kindly, old Emma Spool (Claudia Bryar), a waitress at the diner where Norman had worked. She explains to Norman that she is his birth mother, that she gave Norman to her sister, Mrs. Norma Bates, to raise while she herself spent time in an institution. She explains that she has been doing the killing, disposing of those who would harm her son. It may have been the studio’s plan to restart the timeline by giving viewers Norman’s “real mother” and having his mother issues start all over again. But the next film went in another direction, picking up only a month after the action of this installment.

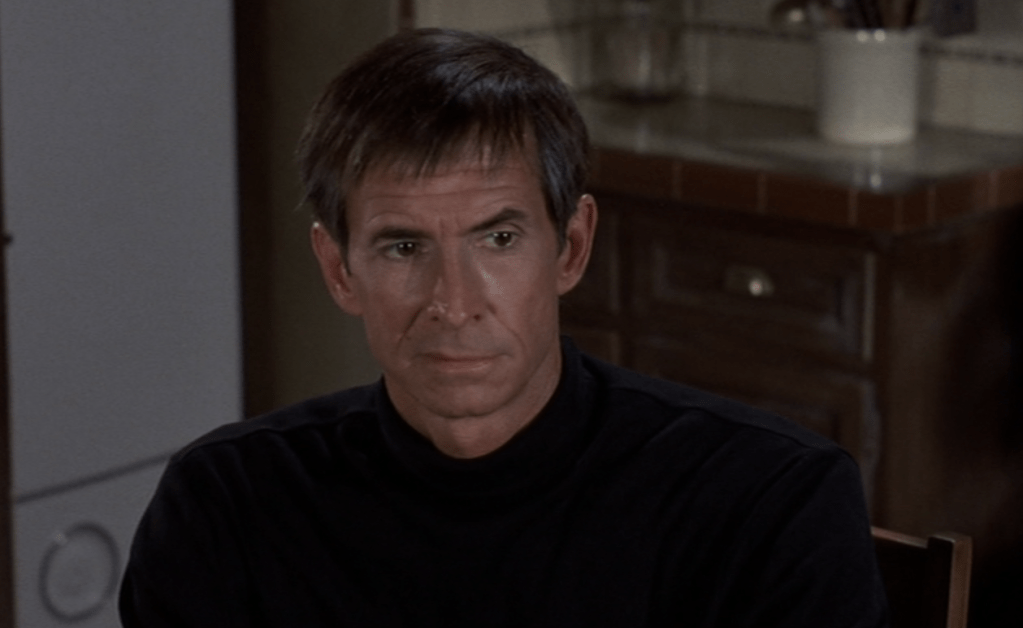

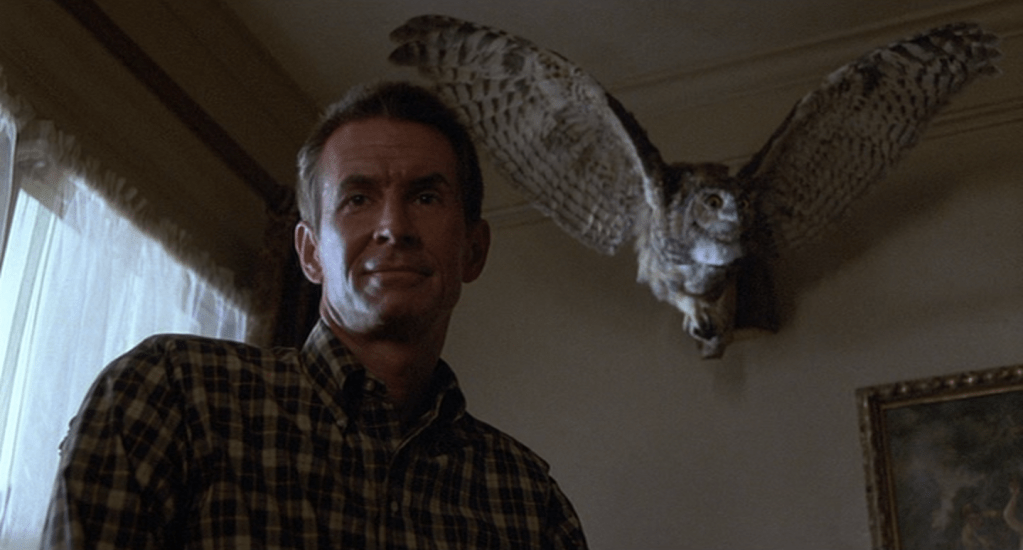

Psycho III (1986) // Directed by Anthony Perkins and co-starring with him are Diana Scarwid and Jeff Fahey

Unhinged young nun Maureen Coyle (Scarwid) is struggling with her faith and severe guilt issues. She abandons her convent and finds herself at the Bates Motel. Mild mannered Norman Bates is still hearing his mother’s voice but he is getting by, passing through society gingerly. Emma Spool is still missing and the search for answers to what happened to her intensifies. A journalist has got the scent and zeroes in on the Bates Motel and its proprietor, Norman. Also of the party is another lowlife-type, Duane Duke (Fahey), who Norman takes on as assistant manager of the motel. Duke learns of the Bates legacy and – when murder again occurs at the hotel – Duke extorts Norman and the two come to blows. Just as Maureen and Norman begin to relate to each other with some tenderness, “Mother” intervenes. Norman Bates, yet again, is pushed to the brink.

Psycho III marks a distinct decline in production value from its predecessor. Interesting that Anthony Perkins was given the director’s reins on this one, allowing him to exert a measure of control over the character that would define his film legacy. Legendary director of photography Bruce Surtees shot this film and apparently “tested” his inexperienced director in the early stages. Perkins, though, proved adept enough to know what he wanted in terms of camera lenses and blocking and Surtees was satisfied. So too were the rest of the cast who found Perkins a gentle man and easy to work with. Sadly, it was while working on this film that Anthony Perkins was diagnosed as HIV-positive.

At this point in the story, Bates is much more tortured than he was in the previous film. Again he is being taken advantage of, harassed and maligned by others who want to capitalize on his past and on his vulnerability – on the suspicion that would inevitably be turned on him should anything go wrong at his motel. And here is what stands out about this film. Yet again it is noted that here is a “slasher” film with a main character who is not the slasher. In fact, here in Psycho III it is driven home that poor Norman Bates is the real victim in the Psycho film arc. He is never – not until the very end – allowed to overcome his mental illness and forge a normal life due in part to his own mental deficiencies but mostly due to the nefarious deeds and motivations of others. Seems it’s always someone else who is getting involved in these stories and doing the killing. This leaves the viewer with a series of films featuring a “killer”…who isn’t.

And here is where the Emma Spool story element dies. Spool as Norman’s real mother is abandoned here as it is explained that Spool had been in love with Norman’s father but he had married not Emma Spool but her sister, Norma. Spool, it is explained, killed Mr. Bates and kidnapped Norman as a child and when Spool was institutionalized, young Norman was returned to his mother. The Spool storyline is a moot point in the Psycho films and is viewed today as a narrative attempt that was simply aborted.

At the end of Psycho III Norman is teetering on the very brink of insanity. It had this time been Spool’s corpse he kept around the house but, when it seemed to be instructing Norman to kill yet again and someone he cared for, he summoned the strength to rebel and destroy the corpse. As he’s put into the back of a police cruiser, he is informed that, this time, he may never see the outside of an institution again. Norman smiles. “But I’ll be free”, he says, “I’ll finally be free”. Free? Nonsense, Norman. We have another film to make.

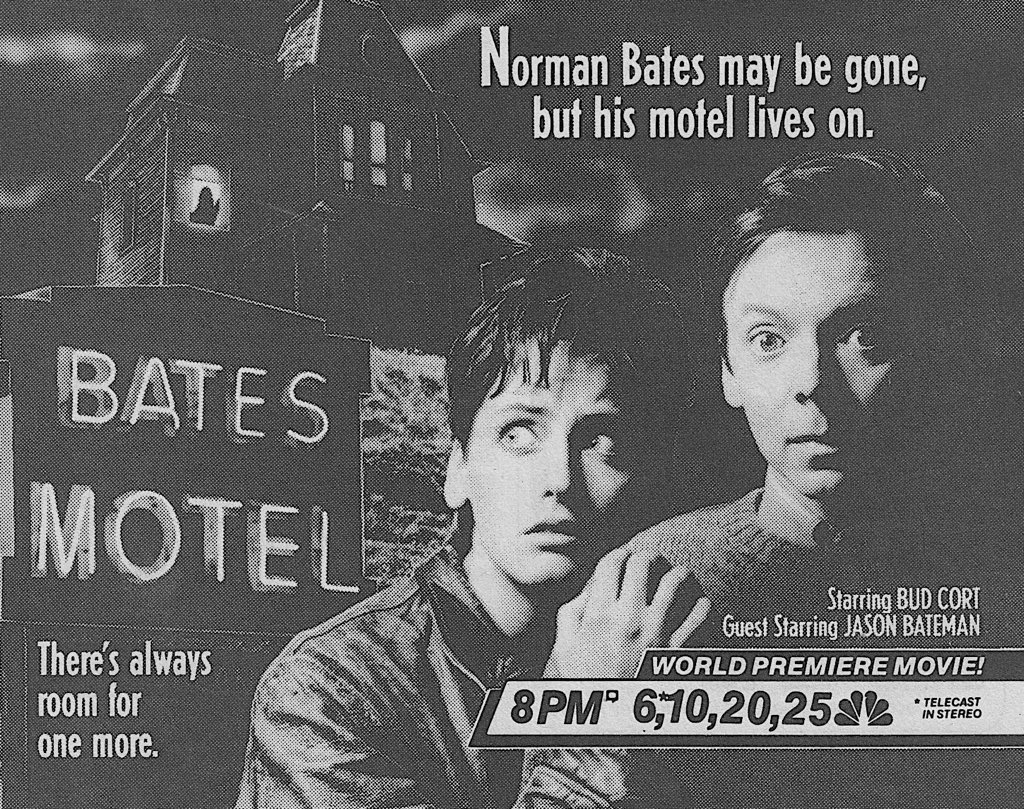

But first we pause to look at a flyer in Norman’s trek, one that isn’t, as they say, canon. Bates Motel is a 1987 TV film that starred Lori Petty, Jason Bateman, Moses Gunn and Kurt Paul, one of only a small handful of men to ever play Norman Bates. Paul was more a stuntman who had doubled for Anthony Perkins and played “Mother” in Psycho II and III. Not only does this film stand alone but it also exists without the presence of Norman Bates. In this story, Bates was never released from the asylum and has passed away. He had a roommate in the sanitarium – played by Bud Cort – who is released and – unbelievably – inherits Bates Motel. This film concerns itself with ghost stories and suicide prevention.

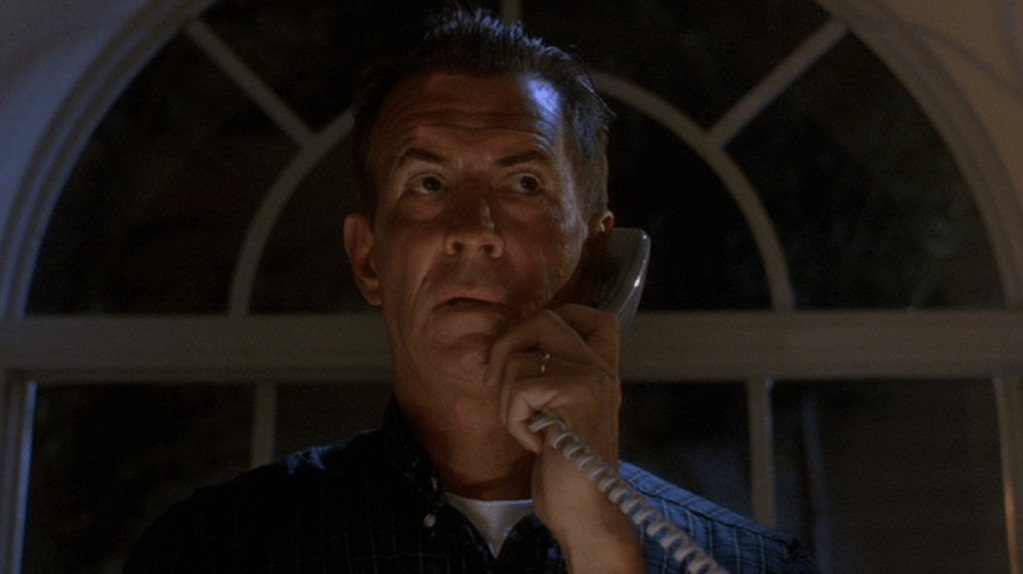

Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990) // Directed by Mick Garris and co-starring with Perkins are Olivia Hussey, Henry Thomas and CCH Pounder

Fran Ambrose (Pounder) has a popular talk radio program. Tonight’s guest is psychologist Dr. Richmond (Warren Frost), a man who once had Norman Bates for a patient. The topic is matricide and Norman is an interested listener. He calls in to talk, using the name “Ed”, and says he has in the past committed matricide and is about to kill again. He tells his story to Ambrose, Richmond and the listeners.

The story Norman tells on the radio is shown to the viewers in flashbacks. Norman describes his young life with his mother, Norma (Hussey), who seems to suffer from schizophrenia and who dominates and brutalizes her son. Norman’s father has long since died and, eventually, Norma takes up with a violent man who also mistreats Norman. Finally, Norman has had enough. He kills his mother and her lover by poisoning their iced tea. Norman at once develops a split personality and assumes his mother’s identity to assuage his guilt. He later “becomes” her to kill two women who come to stay at Bates Motel.

Back in the present day, Dr. Richmond has figured out who he has been talking to on the phone and immediately raises the alarm. Norman’s stated intention to kill again is not taken lightly as it is once again assumed he is more than capable of murder. But the victim this time will not be his mother. The victim? His own wife.

I give this installment points although it is a “TV movie”, one that was made by Universal Television on the Universal lot for Showtime. Interestingly, the movie was written by Joseph Stefano (1922-2006), screenwriter of the original Psycho film. Notable casting choices include Henry Thomas as young Norman and a gorgeous 32-year-old Olivia Hussey as Norma Bates. And somehow director John Landis is on hand to play the producer of the radio show.

It is a well-worn device of any franchise to include an episode that serves as an origin story of how the characters we know so well came to be. Much of what we see transpire between Norman and his mother makes sense in terms of what we know about these characters from the original film.

I feel like it is a major addition to Norman’s story that, in this episode, he is married and to a psychiatrist, at that. Even more interesting is that Norman is about to become a father. The premise of this story is quite sound and casts Norman Bates in the most compassionate light yet. He explains on the phone to Fran Ambrose that he cannot bear the thought of bringing a child into the world. His child. The grandchild of his mother. The baby, Norman is sure, will be “another monster” and Norman thinks he will be doing society a favour by killing his wife so she cannot give birth.

Finally, Norman’s victimhood is on full display in this film and he becomes a wholly sympathetic character. Through the flashbacks, we see how poor Norman got the way he is. His illness is generational, being brought on by his mother’s treatment of him, treatment that has obviously driven him mad. The idea here is that Norman thinks so little of himself as a person – and even less of his progeny – that he feels ready to resort to murdering his wife to stop the madness. Think about that. That is sad and solidifies Norman’s status as a victim.

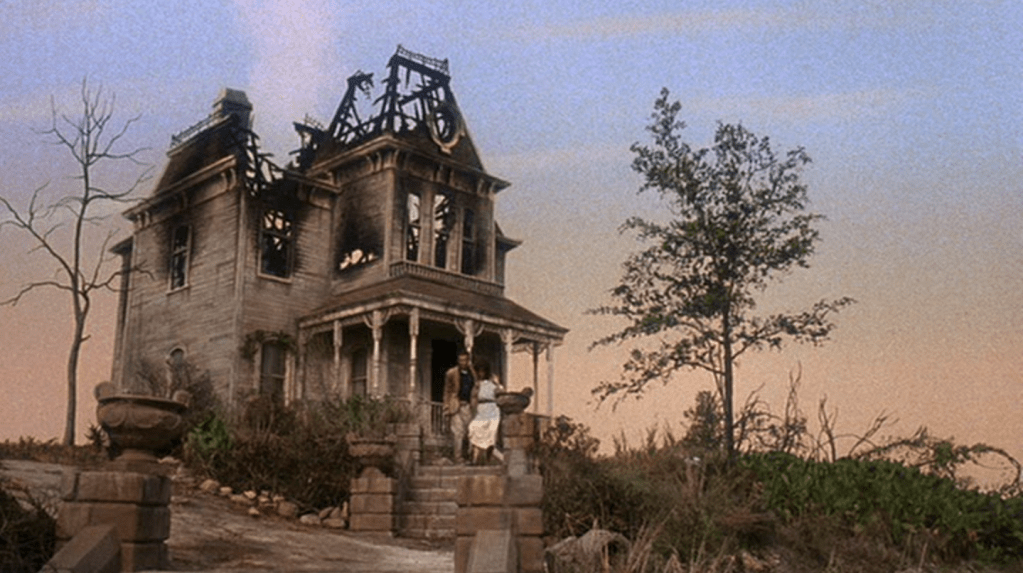

The final scenes are actually quite tense and the pacing is excellent but you never once think that Norman will actually kill his wife. There is a finality to this tale as the Bates home is burned to the ground, freeing Norman from this symbol of his tortured youth. I was intrigued by the closing moments. Norman walks away from his house ablaze and he turns to look back. I wondered what he would see. If he had turned and saw something in a window – a silhouette of his mother or some such trickery – it would have been a somewhat harsh suggestion to the viewer that Norman actually wasn’t free. That would’ve not only left the door open for more films but – more significantly – it would have been a poignant statement that Norman Bates, and, indeed, many others similarly afflicted, will always suffer to some extent from mental illness. But – kindly – the movie lets him off the hook and the film odyssey of Norman Bates ends on a pleasant note. We can believe that he is truly free and is ready to become a father alongside his loving wife.

Now a quick word about further depictions of the Psycho story. In 1998, Gus Van Zant released a shot-for-shot remake of Psycho starring my main man Vince Vaughn as Norman Bates. This was a big deal to me at the time as I was watching Vaughn’s career closely on the heels of his work in Swingers, The Movie That Changed My Life. Vince getting an offer from Spielberg (The Lost World) and then getting tapped to portray an iconic character like Norman Bates put him on the map. As regards the film, right off the bat, sure, it’s easy to ravage the movie and Van Sant and yell “why?! why?!” but at the very least the remake is interesting. What makes it so is that it invokes probing discussion. Roger Ebert didn’t like it but made this typically insightful comment: “(The film) is an invaluable experiment in the theory of cinema, because it demonstrates that a shot-by-shot remake is pointless; genius apparently resides between or beneath the shots, or in chemistry that cannot be timed or counted”. Additionally, Van Sant admitted that his remake was something of an experiment to show that no movie can really be remade shot-for-shot as the tenor of the original – as the venerable Mr. Ebert states – cannot really be captured. So, while this film was not received favourably, it is interesting to see and – as I’m always trying to remind you people – there is something to be gained from the viewing experience. As there is from almost any movie. Remember what Tarantino says; “we didn’t love the movie, we loved watching it”.

Bates Motel remains the longest-running series in A&E’s history. The five-year run of the show depicts Norman’s life with his mother running the motel which has been relocated to Oregon enabling the show to shoot in Vancouver. This iteration seems to absolve Norma Bates somewhat and focuses on Norman’s mental struggles. The part of this series that really interests us is the final season which roughly retells the story of the original film.

Norman befriends Madeleine Loomis, wife of Sam Loomis, who is having an affair with one Marion Crane – portrayed, unbelievably to me – by Rihanna. Marion shows up at the motel to meet Sam and she and Norman have dinner. During the course of the night, Norman informs Marion that Sam is married – something she did not know – and, in a rage, she goes to the Loomis home and smashes Sam’s car windows. And then she leaves town. Alive. It is Sam Loomis who then shows up at Bates Motel. While he waits for Marion, he decides to freshen up. Then, Norman Bates kills Sam Loomis in the shower. So, in the end – to this point – of the cinematic life of Norman Bates, he has killed his mother and Sam Loomis – but not Marion Crane – and is charged with murder. Before his trial begins, Norman is in his family home sitting at the dinner table with his mother’s corpse. Norman’s half-brother, Dylan, shows up and begs Norman to face reality. Norman cannot do that, though, and attacks his brother with a knife. Dylan shoots Norman. As he dies, Norman Bates thanks his brother for reuniting him with his beloved mother. After all, a boy’s best friend is his mother.

But instead let us take as the “canon” end of Norman Bates’ film odyssey the more satisfying finale of Anthony Perkins’ last appearance as Norman in Psycho IV. Much nicer for us to think of Norman free, his family home burned to the ground, the Bates Motel no longer his means of income and his psychiatrist wife expecting his child. For a man who had for so long been the victim as opposed to the perpetrator of the carnage throughout the arc of one of the most iconic stories in cinema and pop culture history, we can all sleep better (if not shower better) knowing he survived and doddered off into old age a contented man, husband and father. As long as none of you wise guys suggests that maybe Norman and his wife had a daughter and everything started all over again but with the genders reversed; Norman the “Father” to a deranged daughter! I can’t believe I even wrote that, planting the seed in your minds.

But all these tales of Norman Bates may simply be moot. I understand that many of you don’t accept any Psycho story that was not directed by Alfred Hitchcock and that is perhaps as it should be. Hitch’s landmark film is truly one for the ages and while these appendages may be of some interest, 1960’s Psycho stands alone – not only among these other works but also alone among only a handful of other of the greatest films ever made.

I might be the only person you know who grinned in delight at seeing the title of your article. I’ve long been a fan of the PSYCHO film series and am greatly intrigued with the character of Norman Bates. Tony Perkins brought the character to life and it was hard to accept anyone else in the role. No other person had those strange yet alluring mannerisms.

Tony had a hard time shaking off the image of Norman and the typecasting got under his skin. He tried for twenty years to redefine himself to moviegoers without much avail. In the end, he embraced the living legacy he had helped create. His directing PSYCHO III was likely both therapeutic and highly enjoyable, as he could revel in this notoriety. A key person who worked with him on all the PSYCHO films was Hilton A. Green, who strove to preserve the Hitchcock “touch”. In fact, PSYCHO II is one of the best sequels that I have ever seen, both in terms of storytelling and in regards to ambiance. I do believe that the Master of Suspense would have approved the continuation of the Bates narrative.

Aside from myself, I often think that I write these articles for only a handful of people; friends I’ve met on the internet, people I don’t know in real life. You, Erica, are one of them. To have you appreciate a piece pleases me so.

I’m pleased, too, to hear that someone else has good things to say about the “other” Psycho films as opposed to dismissing them. They are more than watchable. You make good points about Perkins and what he brought to the role. And you remind me that I wanted to mention Hilton Green – I had spotted his name in the credits of the first film and the sequels. I had wanted to investigate this through line – with Perkins – of these films.

And I’m happy that you enjoyed the article’s title! That was a bit of inspiration. I worried people would think I was referring to “my” life as opposed to Norman’s but I’m glad you got it. And I’m so glad you were here to read and comment. It is appreciated.