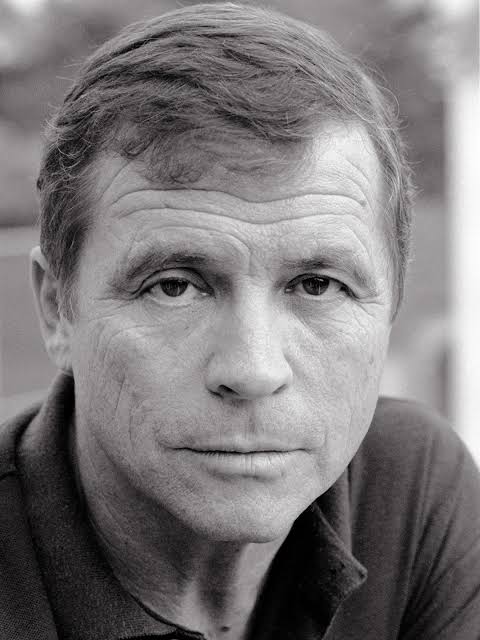

There are 8 million stories in the Vintage Leisureverse and here we try to tell them all. Today we’re looking at yet another outlier, another dissenter, another maverick who found his own unique way to do it, to tell us what he thought we needed to know. If we are to celebrate here those who made the journey the hard way, then we would be remiss not to talk about one Thomas Robert Laughlin, Jr.

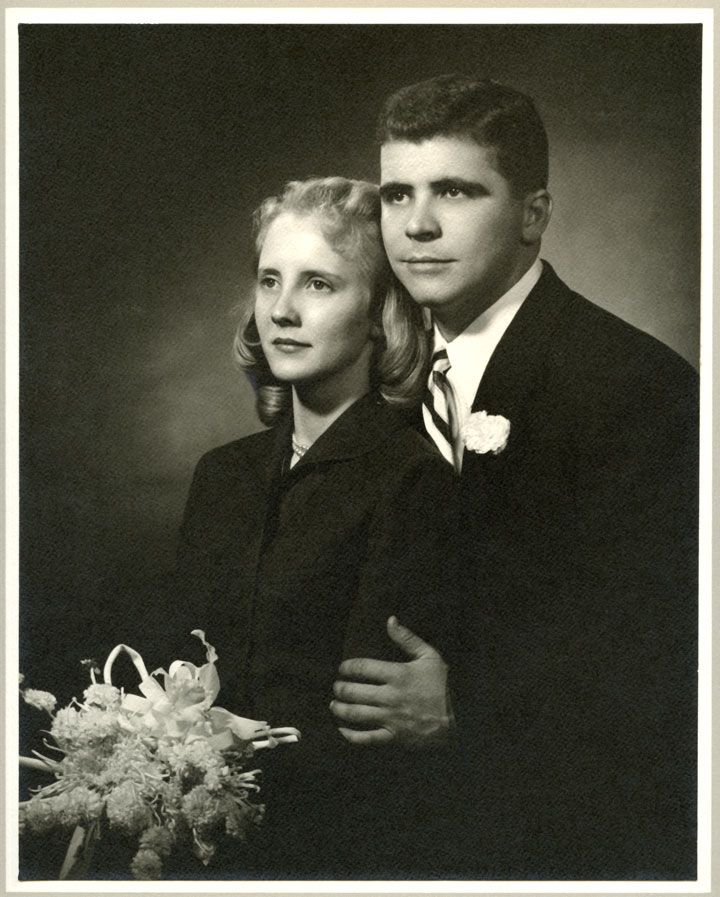

Tom Laughlin was born August 10, 1931 in Milwaukee. After a childhood he described as unsettled, he found some success playing football – safety and halfback – at first the Jesuit Marquette University and later at the University of South Dakota. Also attending the U of SD at this time was Delores Taylor. Taylor was born in Winner, South Dakota and grew up near the Rosebud Indian Reservation. Her father had operated a post office that was frequented by Native Americans and so Delores was familiar with the Indians and the reservation way of life. She was engaged to another man when she met Tom on campus. During the Christmas of 1953 Tom was home with his folks when he made a decision. He hitch hiked to Taylor’s home in South Dakota to talk her out of marriage to the other man. Tom was persuasive and Delores was susceptible. They became a couple and married the following October. Taylor would share her knowledge of Indian affairs with her new husband and this piqued his interest. But first, there were bills to pay.

Laughlin took to acting and appeared as a college boy in Tea and Sympathy (1956) before landing his first starring role in Robert Altman’s feature debut as a writer and as a director, 1957’s The Delinquents and Tom played a Navy pilot in South Pacific (1958). He also paid dues on the small screen with roles on shows including Riverboat starring Burt Reynolds. Then in 1959 he appeared with Cliff Robertson in Battle of the Coral Sea and as Lover Boy in Gidget, the only role for which I knew Laughlin growing up. And then Tommy went outside the lines.

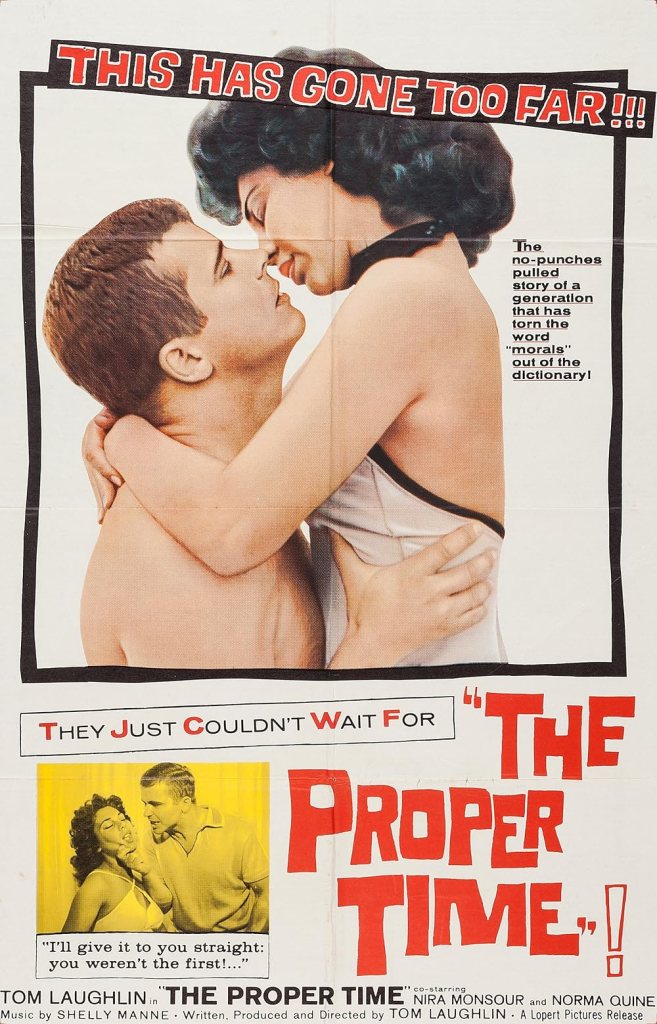

Taking matters into his own hands with a desire to tell the stories Hollywood wasn’t, Tom wrote, directed and starred in The Proper Time, a story of a young student with a speech impediment who gets in a jam with his girlfriend and her roommate on campus at UCLA. News reports of the day tell of Laughlin noticing the kids’ reactions to films like Peyton Place and his assumption that he could tell a story of the sexuality among young adults much more accurately and sympathetically than could “Hollywood’s tired old men”. The papers reported on Tom’s “inner moral” conviction that resulted in the film and of one particular negative review that was protested by students when the film was shown at the University of Santa Clara. “No long-haired angry young Beatnik, Laughlin has lectured to college groups on philosophy, psychology and religion” went one report adding that Tom showed up to the screening in khaki pants and red sweater stating that he could not come formally attired as his black sweater was at the cleaners. So, right from this auspicious debut as a filmmaker – The Proper Time was shot in six days for under $30,000 and was eventually released in 1962 – it is clear that Tom Laughlin was determined to make a mark and do things his own way.

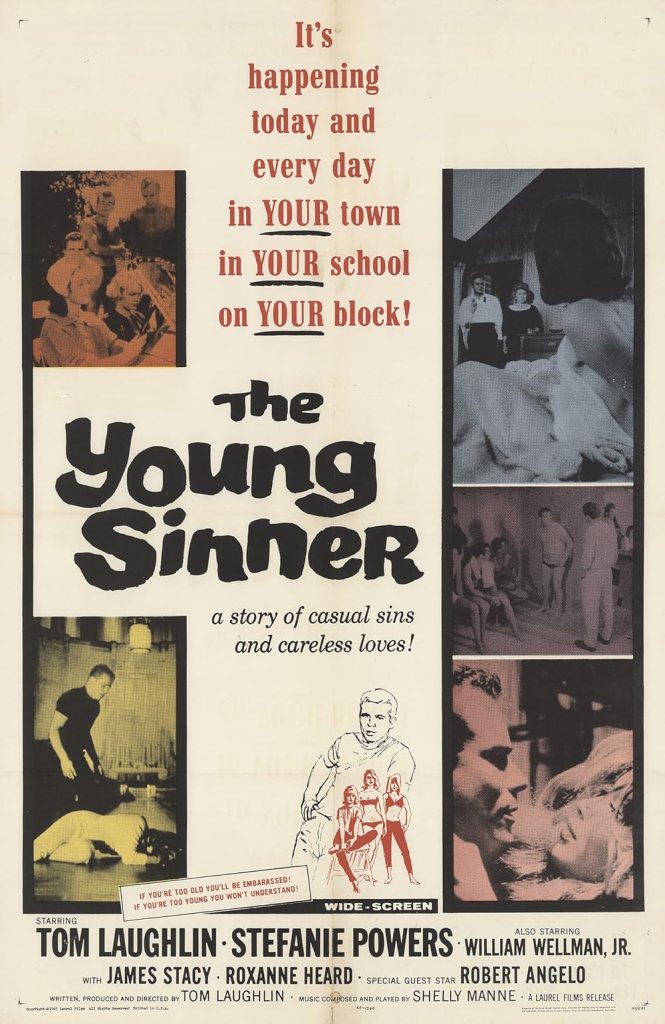

His next time up to the plate was even more ambitious. Tom wrote, directed and starred in The Young Sinner, the story of another student, this time a star high school athlete who gets deeper and deeper into trouble after he is caught in bed with his girlfriend. This one actually co-starred Stefanie Powers, William Wellman, Jr. and James Stacy. But Laughlin’s goal was much more than just making a movie about teenage sex; consider that this film was originally intended to be the first of a trilogy called We Are All Christ.

Who did this guy think he was? Who was he trying to kid, writing and directing his own bold movies? Why did he not just play ball?

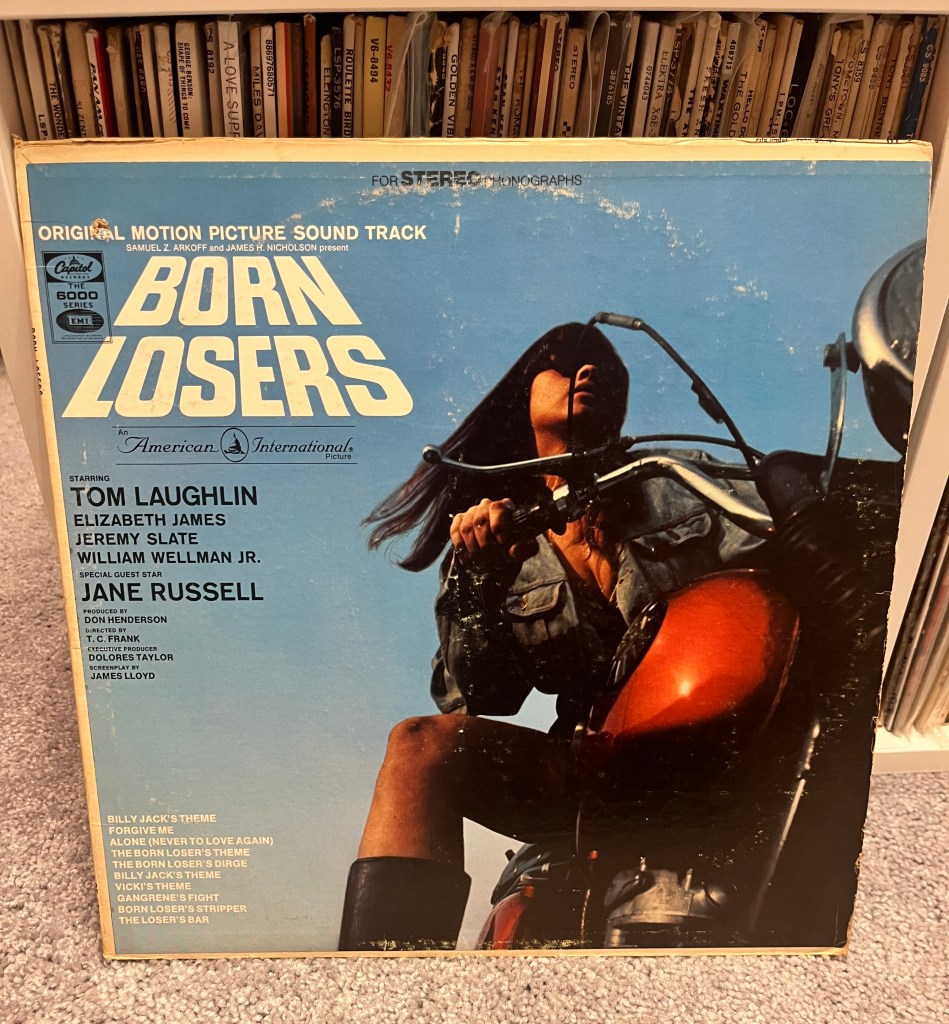

Tom Laughlin “back-doored” his signature character into the public consciousness. Having tried since the mid-Fifties to produce a screenplay featuring Billy Jack, a half-Indigenous American Green Beret war veteran and hapkido expert, Laughlin decided to hitch a ride on the nascent biker film sub genre. Tom directed (billed as T.C. Frank; his noms de plume are legion) and starred in 1967’s The Born Losers, a story based on a real life incident in which two Hell’s Angels were arrested for sexually assaulting two teenage girls in Monterey. In the film, a small town is terrorized by biker gang the Born Losers and only Billy Jack is willing to stand up to them and the ineffective sheriff. The local authorities are too afraid of the bikers to move against them but Billy Jack – as “half Indian” – is singled out for suspicion and hostility. The main female character, Vicky, is played by one Elizabeth James who also provided the script for the film. The somewhat enigmatic writer also appeared in Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry but was not much for films, instead authoring novels. Jeremy Slate and William Wellman, Jr. play bikers and Jane Russell appears briefly as this was a time when she was pointlessly showing up in films like this.

Laughlin ran out of money late in the production and turned to heroes we often run into here at Your Home for Vintage Leisure – American International Pictures. They gave Tom enough money to finish the picture – shot on location in three weeks for a total cost of $160,000 – and when it was released all were surprised to have a hit on their hands.

In The Born Losers, Tom Laughlin portrays Billy Jack as a peaceful man who simply wants to live a life in harmony with nature. He has turned his back on society and lives in solitude in the California Central Coast Mountains. As soon as he returns to civilized society, he promptly comes upon injustice. He calmly attempts to right these wrongs and finds himself in the slammer when The Man jumps to conclusions about him, his attire, his history and his heritage. Billy reverts to his default settings when he is forced to dispatch the gang leader before being accidentally shot by a deputy and left for dead. As he is hauled away on a stretcher, the reformed sheriff and Vicky salute him. The Born Losers was enough of a financial success that it provided the means by which Tom Laughlin could finally tell the story he had long wanted to tell.

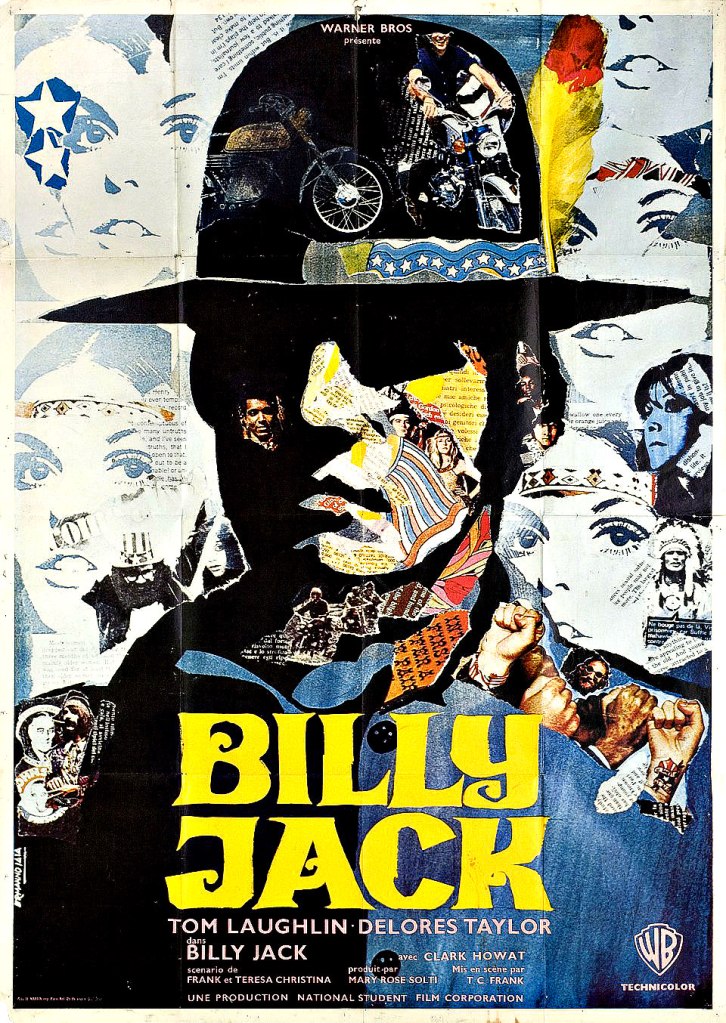

American International gave Tom the money he needed to shoot Billy Jack. After the first ten days of shooting, AIP’s Sam Arkoff and Jim Nicholson looked at what Laughlin had shot and were stunned. Horses. Horses running, galloping. And that was it. The $300k they had fronted Tom was almost gone and Tom had nothing but miles of footage of horses. The parties could not come to an agreement on how to proceed and AIP backed out. Laughlin, distraught, took his film to Fox who wanted to strip him of his creative control but Tom wasn’t having that and eventually Warner Bros agreed to finance the project through to completion. Our maverick filmmaker had the last laugh when Billy Jack was released some 2 years after shooting had started and was a colossal success.

In Billy Jack, the title character is identified as a mixed race Navajo. He has aligned himself with the Freedom School, an alternative (read; “hippie”) school for fringe and troubled kids. Billy Jack defends the school and its director (played by Tom’s wife, Delores who would share the workload with her husband throughout his professional life) from the townspeople who don’t understand these kids and the counterculture in general. The kids are hassled anytime they go in to town.

The story diverts when Billy undergoes a Navajo initiation ceremony in which he receives a rattlesnake bite in an attempt to become blood brother to the snake. The son of the local corrupt politician causes havoc, raping and murdering until he is abruptly stopped by Billy. Of course, the authorities come after Billy who holes up and prepares for a stand off. He eventually surrenders to the police – sacrifices himself – in exchange for a promise that the school can continue to operate for the foreseeable future. Billy Jack is lead away in cuffs while the crowd raises their fists in a show of support.

Billy Jack also features appearances by Bert Freed (Then Came Bronson) and Howard Hesseman (WKRP in Cincinnati). It is undisciplined and runs like several small movies in one; hillbilly townsfolk don’t understand the hippie kids, one denim-clad, motorcycle-riding dude against The Man, vigilantism and violent revenge and anti-Indigenous bigotry with stops at student theatre and an unruly and awkwardly authentic town council meeting. Having said all that the film remains compelling. Laughlin plays Billy calm and cool enough to still appeal to modern audiences and the movie also retains a fresh, bright look aided by the practical locations. And perhaps it should be said that fervent passion never goes out of style. At one point, a frustrated Billy is racing off to let slip the dogs of war and is challenged by pacifist Jean who suggests they can pull up stakes and go where things aren’t like they are here. Billy angrily retorts “tell me, where is that place? Where is it? In what remote corner of this country – no – entire goddamn planet is there a place where men really care about another and really love each other? Now, you tell me where such a place is and I promise you that I’ll never hurt another human being as long as I live”. Another fine moment comes when the deputy threatens to shoot pretty Cindy unless Billy drops his gun. Here Tom Laughlin presages Dirty Harry’s sentiment when he encourages the deputy to shoot her – so that Billy can kill the deputy. It’s a great exchange.

The film was generally panned by critics who complained of many things including Laughlin making a pacific statement with a violent movie, the message being “rammed down the spectators’ throats”, the film being too long, “well-aimed but misguided”, the acting being “incredibly awful”, the film trying “to say too many things in too many ways” with one reviewer calling it “horrendously self-righteous”. I was particularly drawn to the review by David Wilson of The Monthly Film Bulletin who said “there is enough innocent sincerity in the film to demonstrate that Tom Laughlin at least has the courage of his convictions, even if those convictions are scarcely thought out”. Tarantino loves critic Kevin Thomas who dissented and said in the Los Angeles Times that the film is “crude and sensational yet urgent and pertinent…this provocative Warners release is in its unique, awkward way one of the year’s important pictures”. All this aside, by 2007, Billy Jack was considered the most successful independent film of all-time when adjusted for inflation.

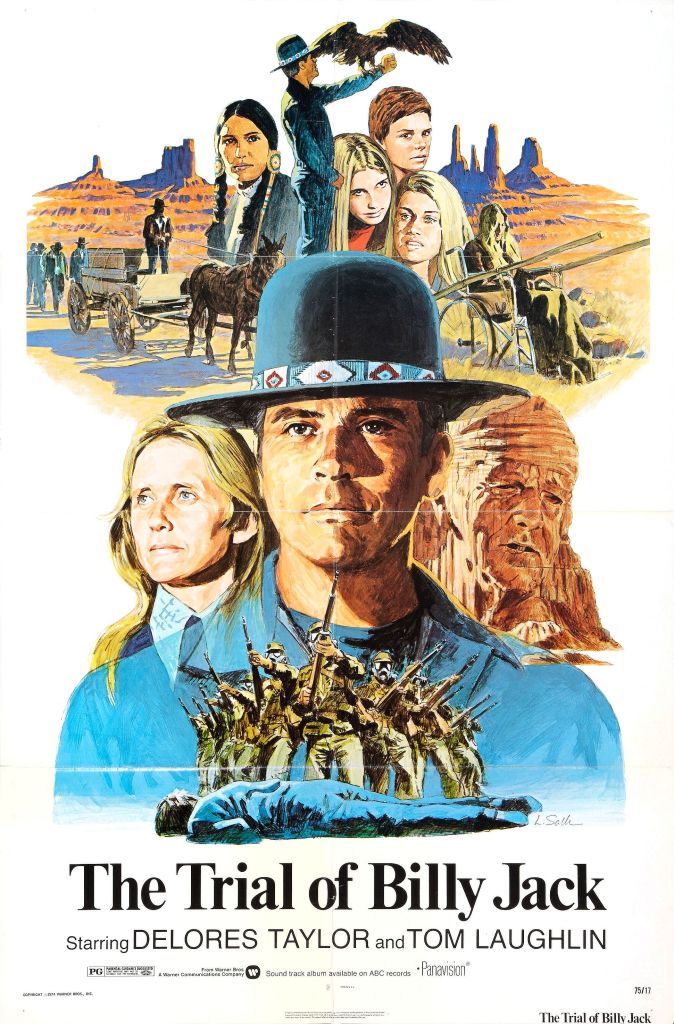

As summer 1973 came to a close, Billy Jack’s odyssey was only half over. Tom Laughlin was just getting started, really. Billy Jack’s third adventure was captured in The Trial of Billy Jack and with this film Laughlin really indulged himself making a sometimes surrealistic and often meandering 173-minute magnum opus featuring counterculture school kids fighting the system, vision quests, hapkido, Jungian psychology, child abuse, FBI surveillance and yes, violence. Speaking cynically, the film is a bloated, political tract that Laughlin used to espouse his views on the state of the union at the time. But looked at in a different light it is an earnest attempt to shed light on what Tom perceived as horrible injustices perpetrated by an unchecked government. Often when these stances are taken in film the results are simply tedious as it is often felt that a film that is entertaining for the general public has been sacrificed on the altar of “making a statement” which satisfies more the filmmaker than it does the audience.

Filming his own script again, Tom had returned to AIP and the studio financed the picture. But when it came time to distribute the film, the two had another falling out. Tom Laughlin then made history when he conceived a unique plan for the release of The Trial of Billy Jack. Instead of the usual practice of releasing a film in a few select cities before spreading it across the country, Laughlin handled his own distribution and had the movie released all across the nation on the same day. This combined with widespread commercials aired during national news broadcasts helped spread the word and set the standard for the promotion and release of films going forward. As a result of all this, it is said that The Trial of Billy Jack is the “first blockbuster” and this is down to the vision of Tom Laughlin.

If all this wasn’t enough, this second sequel was a huge commercial success. I’ve talked about Laughlin’s indulgence and the danger of a “message” film alienating an audience. Well, this was certainly not the case with The Trial of Billy Jack and a film made outside the studio system that would eventually gross some $35 million must’ve got something right. Laughlin later said quite candidly that if he had it to do again, he would’ve shot parts of the film differently, tightening up many of the scenes. But with all of its faults it captured the audience’s fancy and obviously struck a chord reflecting the atmosphere in the country at the time. Incidentally, watch for William Wellman, Jr. again and the infamous Sacheen Littlefeather.

The press was in rare form in reviews of The Trial of Billy Jack:

- “three hours of naiveté”

- “badly in need of trimming its 170-minutes running time”

- “gross, misleading and a run-on bore”

- “one of the longest, slowest, most pretentious and self-congratulatory ego trips ever put to film. The running time is an excruciating three hours, which make you wonder what the five count ’em five credited editors did for their pay”

- “this film probably represents the most extraordinary display of sanctimonious self-aggrandizement the screen has ever known”

- “this sequel proved more of a trial for me than it was for Billy”

- “laughable”

- “ludicrous”

Tom Laughlin then wrote and directed The Master Gunfighter, released in October of 1975 and Tom’s only film since The Born Losers not to feature Billy Jack. Tom starred as Finley, a master swordsman and gunfighter, who is caught in the middle of a land war between the unscrupulous US government and wealthy Latino ranchers. Again Laughlin shines a light on racial injustice and again he makes a dishevelled film that was savaged by critics – again, Kevin Thomas excepted. This time the complaints range from “hapless”, “long, stilted, self-conscious, badly acted and boring” and “contemporary bleeding heart attitudes” to “sanctimonious”, “confused, incoherent action and stilted acting” and “the audience will be in a coma”. The film lost a ton of money so Laughlin was pleased to later receive a call from a legendary director’s son.

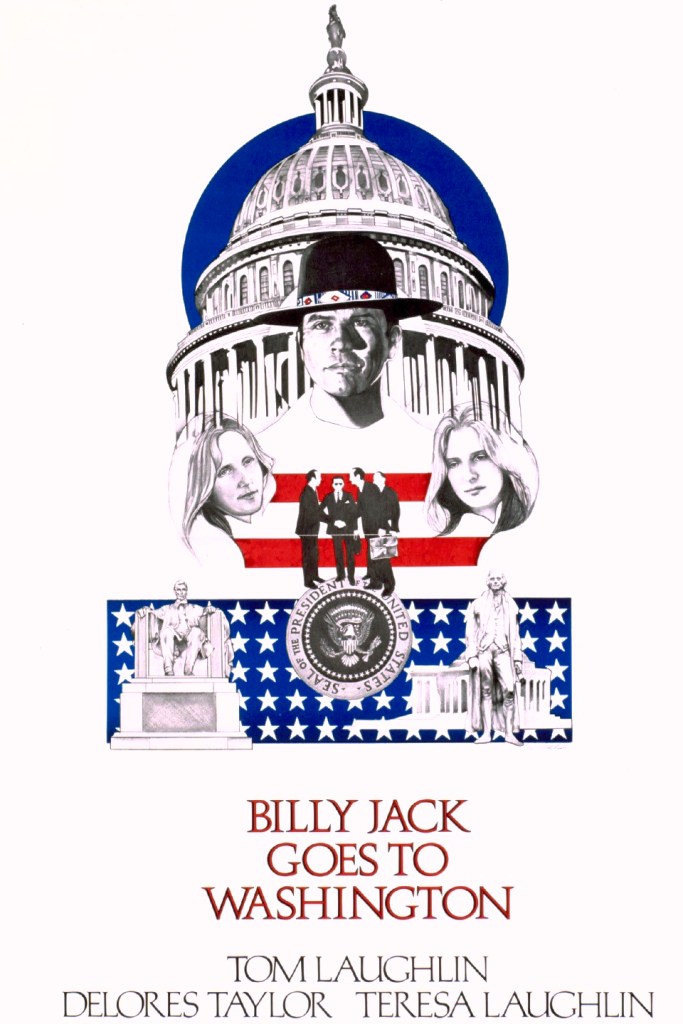

For some reason, Frank Capra, Jr. had long wanted to remake his father’s film, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington as a Billy Jack movie. Lucie Arnaz and Sam Wanamaker join Laughlin in this film that proved a bridge too far for the ballad of Billy Jack. This fourth installment was a failure due in part to the character stepping out of his usual milieu and appearing in sedate settings while wearing a jacket and tie. And without much of the Billy Jack aura in the film, audiences were left with just the Laughlin ideology and maybe people had just had enough. People were perhaps more accepting of what Laughlin had to say when he was dressed in denim and stoically ready to throw down against the villains and kick guys in the head. Granted it didn’t help that the film suffered severe distribution problems, failing to make it into many theatres across the country – something Laughlin attributed to “the film being blackballed under pressure from politicians involved with nuclear power”. Washington proved to be the final frontier for Billy Jack, the film’s 155 minutes somewhat of an ignominious end for the celluloid rebel.

Tom Laughlin never quit. In late 1985 and into ’86, he started making The Return of Billy Jack, in which Billy goes up against child pornographers. However, early into filming on the streets of my hometown of Toronto, Tom suffered a concussion and the production shut down never to get back on track. Tom never let the idea of another film rest though and in 2004 he attempted to get one rolling but this time under a new title, Billy Jack’s Crusade to End the War in Iraq and Restore America to Its Moral Purpose, in ’06 as Billy Jack’s Moral Revolution and then in ’08 as Billy Jack for President and then Billy Jack and Jean. At this time, Laughlin reported that the film would create a whole new genre dealing with “social commentary on politics, religion, and psychology“. A fifth film was never made.

It shouldn’t be surprising that Tom Laughlin ran for president in the 1990s and 2000s as both a Democrat and a Republican. He garnered little support and was always seen as a fringe candidate. Tom later fought cancer, celiac disease, auto immune disorder and suffered a series of strokes. He eventually succumbed to pneumonia in 2013. He was 82. Right up until the end, Tom Laughlin was posting on his website that he had plans for another Billy Jack film.

Tom Laughlin is famous today for having created and portrayed the character Billy Jack. Billy Jack is some percentage of Native American; enough so that Billy is regularly aligned with the plight of Native Americans and shares in their sufferings. Tom Laughlin is not Native American – though AIP chief Sam Arkoff thought that Tom began to think he really was. There’s a name for portraying someone of another race nowadays and the practice is considered offensive. Tom Laughlin and his wife, Delores, witnessed the treatment of Indians and were appalled. The argument would go that the Laughlins – despite any claims to a percentage of Indian blood, which I don’t think they ever made – were not Indians but white and therefore able to partake of all that America had to offer. Who are they, one might ask, to claim to be Native and to take up their cause?

They sympathized with the plight of the American Indian but more than that they were outraged and disgusted by what the treatment of these people said about their government and the country that was their home, the country they loved. It is a gross understatement to say that Tom Laughlin wanted to “say something” and Laughlin felt that the best way to get that done was for him to play someone with Native blood. Could they have found financing to make a film in 1967 with an unknown Indigenous actor in the role? No, they couldn’t and so the story could not be told at all unless Tom played the role himself. Out of necessity. It was that or nothing.

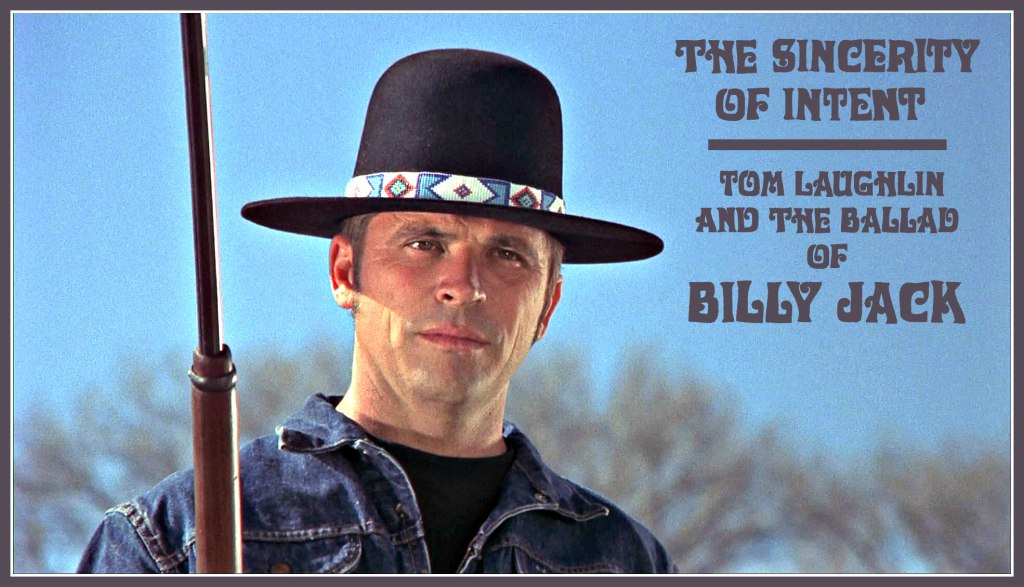

There’s a big difference between Tom Laughlin as Billy Jack and Mickey Rooney as Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and the difference is intent. In the case of Laughlin and Billy Jack, we need to consider the time, the statement and the sincerity of his intent. Tom Laughlin was able to make his statement regarding the treatment of Native Americans because he played one. Millions saw his films and were educated about injustices because he played an Indian. Americans began to reconsider their history because he played an Indian. Americans became mobilized and enlightened about what had happened and about what was going on because he played an Indian. Americans – and indeed audiences the world over – became better aware of this bigotry and maybe their own way of thinking because he played an Indian. And maybe some things began to change because Tom Laughlin played Billy Jack, a half-Navajo Indian.

This was not careless cultural appropriation for entertainment’s sake or for a few laughs. This is one man saying “I have the name and the face and the message. I have the message but only my name and face will get it out there”. In the second film, Billy Jack says “being an Indian is not a matter of blood. It’s a way of life” so what of someone caring so much about a race of people? Or even someone being interested in a way of life to the extent that they immerse themselves in it and get to know it so well that maybe they can begin to feel and understand some of the things felt and experienced by that people? What about an understanding – a cultural appreciation? We must consider that this is something that does exist. Cannot a member of one race understand another? Maybe not fully but enough or somewhat? Does the sincere effort and intent of Tom Laughlin not count for something? I think it does. I think it counts for a lot.

Tom Laughlin was a rebel just as Billy Jack was a rebel. The appeal of the character must certainly have been that he went up against villainy at every turn whether it be savage bikers or corrupt politicians. Billy Jack – the film and indeed the whole phenomenon – is a real paradox. There is a definite coolness inherent, woven into the movie and the character. But there is also present an undeniable…foolishness, for lack of a better word. Taken as films, the Billy Jack movies are severely flawed, even onerous. But as cultural and ephemeral statements they are fascinating. If they were smooth and polished something may have been lost but they were daring and their brokenness made them fun and they were edifying at the same time. Critical opinions may count for something but the film industry needs mavericks like Tom Laughlin who are intent on doing things their own way and not just falling in line with Hollywood power brokers and bean counters. Viewers today may snicker at what is perceived as goofiness in the movies but many still can’t look away.

And it must be said that it can become boring when someone is so opinionated and devoted to fighting the system, taking a stance and sharing their views with others so vigorously. But at the same time we can be grateful. All of us who are content to coast and not stare too long into the blinding sun of the ills of the world are somewhat glad there are fighters like Tom Laughlin.

Sources

- Collegiate Drama Joins Hotter-Than-Ever Trend – Florence Times Daily, December 23, 1959

- Democrat Ladies ‘Insulted’ – Pittsburgh Press, December 3, 1960

- Flying Through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants: From the Man Who Brought You I Was a Teenage Werewolf and Muscle Beach Party – Sam Arkoff with Richard Trubo (1992)

Was it feature films or nothing for Laughlin? I remember him vaguely from the 70’s; he had the good looks and charisma to fit in on any number of hit TV cop shows during that time. It would have bought him steady cash flow to fund his more ambitious projects.

See how smart my readers are? That’s an excellent point. That was money there waiting to be claimed. We all know how many actors made a fine living doing nothing but guest spots. I wonder if maybe Tom was too focused on his own projects and couldn’t think of succumbing to the direction or the vision of another.

But yeah great point. Think of the “lesser” projects Coppola took on in order to finance his dream pictures…

I feel like these films would be more accessible- and I’m a fan of them- with just some mild editing. That’s what Laughlin needed, I feel.

There’s also the repeat of Laughlin getting shot and wounded in Born Losers, Billy Jack, and Trial- I don’t believe the character gets shot in the Goes to Washington film- that I think could have been avoided if Laughlin had a sounding board to bounce ideas off of. He’s a captivating auteur, though.

One thing about Billy Jack that I thought was extraordinary is right before his blow up in the ice cream parlor: Billy Jack’s empathy for the child that was humiliated and how he articulates that, due to some clowning from the local rich kids, this one child will always carry anguish over this memory- that, to me, is really remarkable since, in most (if not all) action/martial arts films, the victims really exist as a device to spur the hero into destroying baddies with his badassery. There was a little more to that scene and I always thought Laughlin should get credit for it.

Couple of great points. Editing is not just cutting film and taping it back together. It is so much about pace and in fact the editor can have as much of an impact on the finished film as the director can.

You also make a very good point about the way Laughlin depicted the victims in these films.

I always welcome lucid comments like yours. Come back any time!!

Hey, I’m a big fan of Gary Wells! SoulRideBlog and Travsd are some of the best pop culture/entertainment history blogs around and I send both to friends on a regular basis. Thanks for all of your great articles.

Oh, man. Such kind words. I always say that I would “do this anyways” but its so nice to know that there are some out there reading and enjoying.

Thanks so much!