“It was not a business negotiation, it was psychological warfare. Morris had to first make you understand that he knew he owed you money, and that you were not going to get it if he didn’t feel like giving it. With me, he knew when to throw a bone, but there was never any doubt who was in control, and he made me aware of this a hundred times, that I was not going to be treated like a respected artist, like a human being. A few thousand here, a few thousand there; that was the closest I ever got to royalties.”

Me, the Mob, and the Music: One Helluva Ride with Tommy James and the Shondells

by Tommy James with Martin Fitzpatrick (2010)

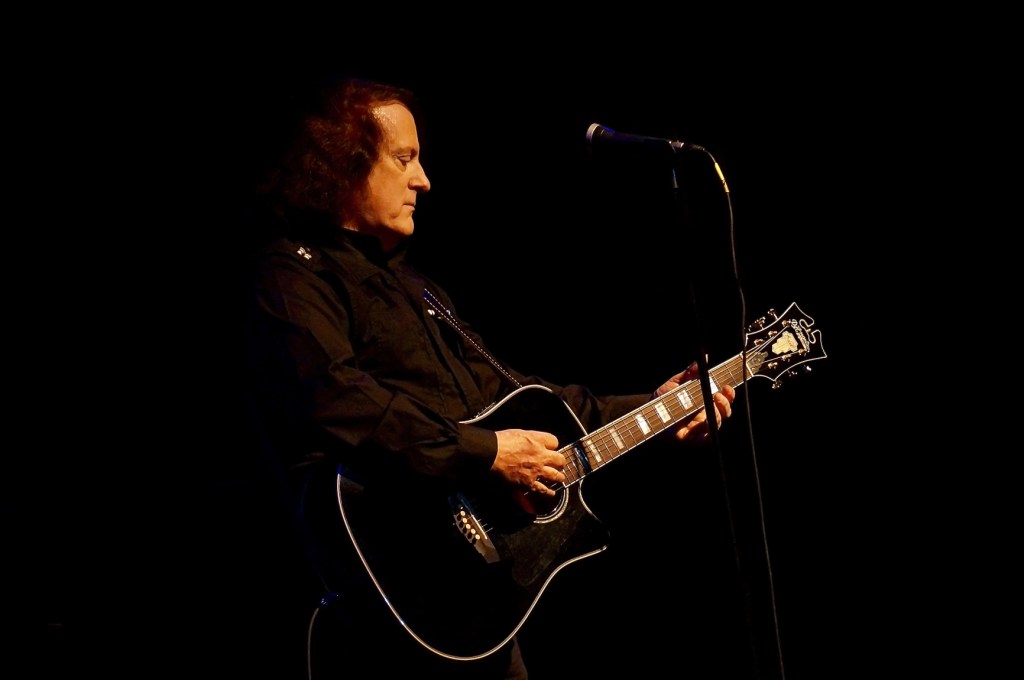

Tommy James and I go way back. I hold dear the memories I have of listening to his music when I was a teenager in the early 1990s. I’ve carried him with me all these years and – in addition to all the great music – he has really come to mean something to me. Just about every spring for the last 30 years I’ve listened to my Anthology cassette – or more recently CD – and then finally I purchased all of his albums on the excellent Celebration box set and wrote about my love for him here at Vintage Leisure – get that story here. It was around this same time that I made the overdue purchase of Tommy’s book. Let’s take a look at it now.

James keeps it light and simple with this engaging memoir. He tells the story of becoming the leader of one of the most popular and consistent American bands of the 1960s and he tells it in swift, unfettered prose. He starts with talk about his early life in Niles, Michigan, of the effect on him of his first radio and of his time spent as a young model. He got his start in his first band when he was 12 and – fittingly – the nascent unit would practice in a friend’s garage. The next significant milestone came when James got a job at the local record store. Here, he learned the business and was able to keep up with all the new sounds, the new bands and the new names that were flying around the local music scene. An early band of Tommy’s got a chance to record and, though they had their own material, they were told what song they would do and James here experienced his first taste of corruption in the business. There was much more to come.

Tommy relates the fascinating story of the recording of his first hit, “Hanky Panky”; of the pick-up band with whom he made the record, of how, months later, a bootlegged version of the 45 became a hit and of James having to assemble a new band to perform live. The story of “Hanky Panky” alone makes Tommy’s tale intriguing. And then there’s Morris Levy.

“Oddly enough, a few royalty statements were paid out regularly. They were royalties owed to that famous songwriter Morris Levy. If you weren’t careful, Morris’s writing credits would appear on songs that were actually written and recorded months before the record was purchased by Roulette.”

Much of the story of Tommy James has to do with Levy, an entrepreneur, night club owner and record executive who had deep ties to organized crime. Levy owned Roulette Records and James explains how Roulette came to sign Tommy and the Shondells. After a day of visiting labels, each one expressed interest in signing the band and picking up “Hanky Panky”. The next day, though, each label had politely declined – each had been scared off by Levy and his Mob connections; “this is my f****** record! Leave it alone”.

James then lays out a riveting two-sided tale – one of pop music success in the 1960s and one of organized crime’s grip on the music business. Specifically, he provides a history of Morris Levy and how he became so powerful and James does it in brisk, simply stated passages that make this book infinitely readable. Many will know that Morris Levy was the inspiration for the character Hesh on The Sopranos. James, then, laments that he was getting no artistic help from his label and little from his bandmates. He alone – with many and varied collaborators – was the well from which product would spring.

“Morris thought and reacted to music like the common man. He couldn’t tell you how to make a hit but he knew one when he heard it, and that’s not as elementary as it sounds. His gift was being able to market the stuff. Nobody was better at marketing rock & roll than Morris Levy. He was also a bully, so whatever he couldn’t do in a businesslike way, he would grab you by the collar and threaten you. That’s how he closed the deal.”

It’s an old story; James tells of having to record songs for which Levy held the publishing and of collaborators like Ritchie Cordell bristling at such arrangements. James also provides some good details on how he wrote songs and delves into his personal life, as well, which was affected by the travails of his professional life. With little money coming in – only from touring, revenue that Levy had no claim on – band mates were not fully compensated and subsequently quit. The strain on his marriages lead James to turn to drugs.

TJ reports that Morris Levy really ran Roulette like it was a crime family with music. Levy would do favours for his artists but then you would be in his debt. Amazing to consider that Levy simply DID NOT pay royalties to his artists. The distribution of records by Tommy James and the Shondells was also hampered by the fact that Levy would not deal with major distributors who would expect integrity in accounting matters. Smaller, shadier distributors were made to take enough records so as to ensure “platinum” sales numbers. In fact, at one point, the IRS were given their own office at Roulette’s headquarters because of how regularly they pored over Levy’s books, looking for ways to hang crimes on the mogul.

It can’t be overstated how interesting it is, this relationship between James and Levy, Tommy even saying that he loved Morris Levy even though he robbed him. Eventually, James employed a lawyer to negotiate a new deal with Levy – one that involved actual payments – and James re-signed with Roulette. After a while, though, Levy simply abandoned the agreement and things reverted to the way they were – “what are you gonna do about it?” However, James goes so far as to say that leaving Roulette would have made him feel like an “orphan”.

“No matter how insane the situation was, how insane the world of Morris Levy was, we realized it still had been the best time of our lives. I missed Roulette and the electricity of the place. I missed the sixties…part of me missed the insanity, excitement, power, glamour, and danger of it all.”

Levy eventually had to leave the country due to violent disputes with rival gang families. James also was told that he should go into hiding as Levy’s enemies may attempt to harm Levy’s cash cow. I’m not sure how many singers have had to take it on the lam to avoid getting kidnapped or killed. Finally, Tommy describes how he came to the decision to simply stop making music – providing no product to Roulette, product that would have made them money but not Tommy. Tommy – who was born Tom Jackson – says he had to “kill” Tommy James; “the only way I could beat Morris was to sabotage my own career. I could have sued him but Morris didn’t care about lawsuits. Morris was a law unto himself. And when it came down to it, you weren’t just fighting Morris. You were fighting all of them, the whole Genovese crime family. And they had no problem shooting their own people. What would they care about a long-haired rocker and his accountant? I was the one who would have to destroy Tommy James. If I didn’t, whatever was left of Tommy Jackson would not survive.”

Nuggets include: Tommy puts the amount of royalties he was not paid at $40 million, the Shondells played an early gig with the Animals and TJ found Eric & Co. to be “belligerent”, James shares a great story of inadvertently creating “bubblegum” music and later describes well the switch to a psychedelic sound, Tommy James and the Shondells toured the States with Hubert Humphrey but when these dates required them to cancel appearances in Britain, stations in the UK simply stopped playing their records, James once almost punched out a drunken Lee Majors and the story is true about James being in far-away Hawaii when he got the invite to play Woodstock, described to him as some gig on a pig farm. He declined and this leads to a cool story about boarding a plane home with a bucket of fried chicken and a .22 automatic pistol.

To simply say this story is unique does not do it justice. For all of his hit-making years, Tommy James recorded for a record label ran by a well-connected member of a powerful crime family. The reader can’t be blamed for a feeling of disbelief but Tommy really did bond with this volatile man and came to love him. And though he was a top pop music star who sold scores of records, he – amazingly – was not paid royalties. More amazingly, when their relationship was over, Tommy says he missed it – despite receiving no accurate compensation for his music until Rhino bought Roulette in the Eighties and issued Shondells music on CD. By that point James had been through Betty Ford’s clinic and had discovered faith in Jesus Christ.

This then is a story of the music business of the 1960s, a story of organized crime and the story of an unlikely bromance. Tommy James is a real survivor and Me, the Mob, and the Music is an amazing rock & roll fable.

Thank you for this insightful book review. I have been interested in Tommy’s book ever since first hearing him mention it on his show on SiriusXM 60s Gold. What a fascinating story – especially for someone interested in both rock music and mob history. Considering Tommy’s “love” for Levy… sounds possibly like a textbook example of the Stockholm Syndrome.

Yes, you make a good point about a “victim’s” love for the victimizer. This might serve as a third level this book works on. Is there a deep psychological reason Tommy felt that way towards Levy? Or is it more the phenomenon I notice in my own life so often – the idea that any situation or relationship, no matter how corrupting or harmful, will take on a rosy glow once it is over and passes into “memory”? Sometimes I will recall old times fondly only to remind myself that I didn’t enjoy them while they were happening. Thanks for reading and for commenting. I always respect your opinion.

Great and thought-provoking review on a number of levels, in human and relationship terms as well as ‘business’. Interesting how we often look at Colonel Parker as the cartoon villain in terms of music and talent managers, with good reason to a point, but this tends to reinforce how well protected Elvis actually was from some of the worst aspects of the music and entertainment industry. The protection obviously came at a price, creatively and financially, but what might have been the alternative?

Seems no performer was safe back in the day. Bono from U2 has often said to the effect that one of Elvis’ main contributions is that his was a cautionary tale and those who came after learned from him what not to do in terms of representation and selling your soul. Add Tommy James to the list of artists robbed in this way.

Very cool story about Tommy James, I heard his music along with other 50’s & 60’s artists, in the late 70’s, still somewhat fresh yet considered “oldies but goodies” How interesting & fun those time must have been, yet truely seems not much has changed, the ugliness of Humanity seems to creep it’s way into everything. Also, glad to see Tommy’s introduction to his True Creator was one of comfort & guidance, sometimes/all times that’s all we have.

CAW